There’s something electrifying about a place that holds centuries in a single room—where fractured marble and glinting bronze become more than just relics. They become evidence. Evidence of stories, of reverence, of gods feared and rulers fallen. Antalya’s Archaeological Museum is one such place.

The Archaeological Museum is where the best of the best has ended up. Not behind glass for distance, but displayed in a way that feels alive: vibrant, eerie, mesmerizing.

For anyone exploring Turkey’s ancient cities—Perge, Aspendos, Side, or Termessos—this museum is an essential counterpoint. In many cases, the most intricate sculptures, mosaics, and sacred objects have been moved here for preservation, making the museum not just a container of history, but a vibrant continuation of it.

Entering the past

You reach the museum by tram—ride it to its final stop in this direction, and the museum is just across the road. Unassuming from the outside, the building gives little indication of the sheer density of its interior.

Inside, the collection unfolds in rhythms. First, with shards and vessels—everyday pottery that once held oil, wine, or water. Then, it swells into form: busts of emperors, fragments of deities, tools, coins, and ceremonial masks. Eventually, you’ll be surrounded by towering sarcophagi, flanked by gods with vacant eyes, and watched by marble faces that seem frozen mid-thought.

Roman sarcophagi carved with winged figures, garlands, and mythic masks

There are rooms that feel quiet and reverent. Others hum with motion. When we visited, we found artists sketching statues, catching in pencil the same light and shadow that once moved across marble centuries ago.

Artists sketching the museum’s sculptures

It was a reminder that this place isn’t just about what was. It’s about what still is.

The hollow gaze

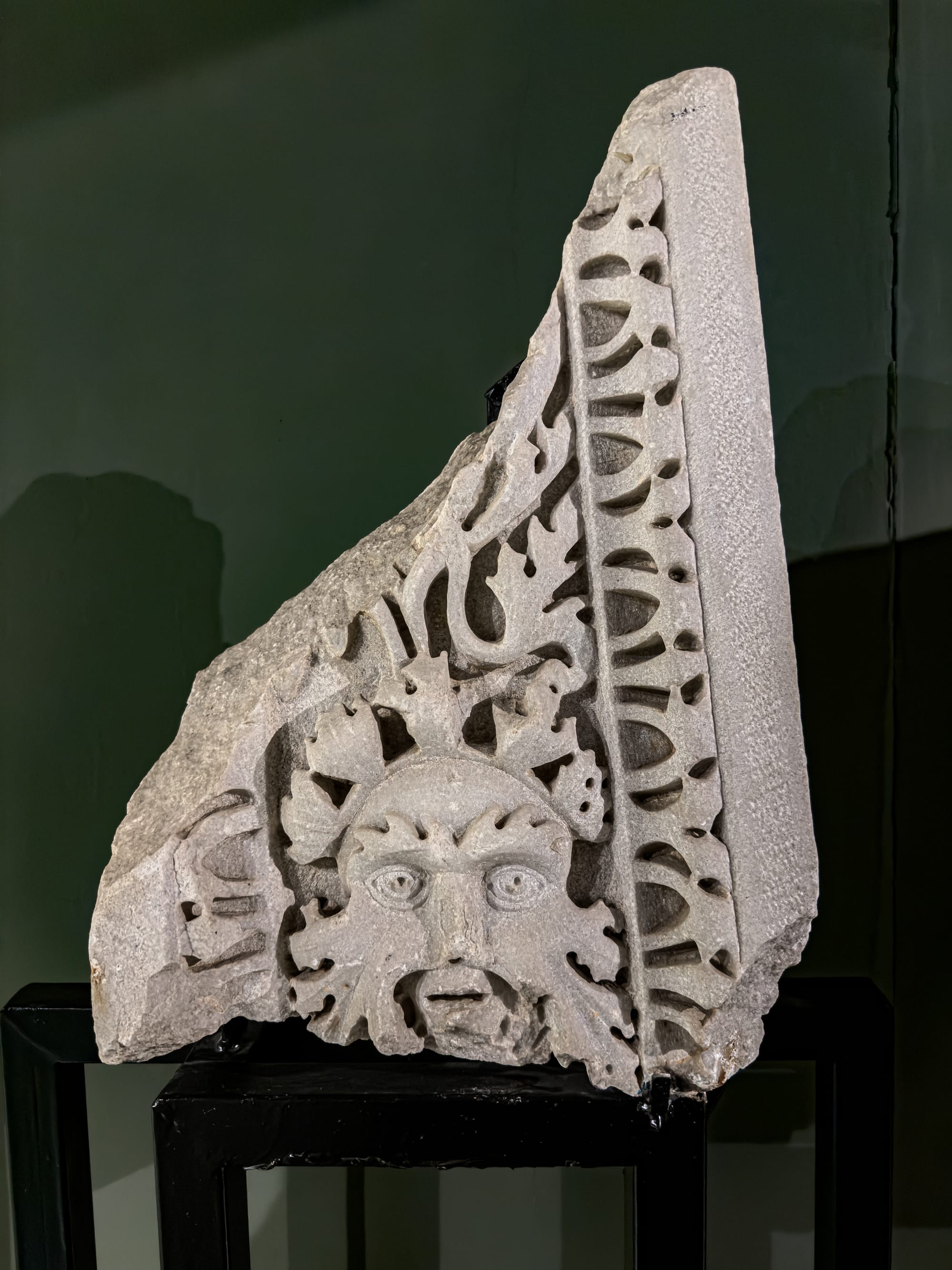

One of the most haunting throughlines in the museum’s collection is the presence of theatrical masks and stylized faces—many with exaggerated, open-mouthed expressions and hollow, circular eyes. These faces seem almost caught in mid-scream or wonder, like ancient renditions of Edvard Munch’s "The Scream."

Some belonged to statues, others to relief carvings, friezes, or sarcophagi. Many originated from theaters, where masks were not only used in performance, but carved into the architecture itself. These expressive visages served both symbolic and functional purposes: to amplify emotion, signal character, or protect against the evil eye.

Fragmented faces with wide eyes and open mouths—ancient drama cast in stone

There’s something strangely contemporary in their design—a surreal blend of myth and psychology.

A museum of many mediums

The museum’s diversity isn’t just in its chronology or geography—it’s in the materials, techniques, and visual languages that collide within its walls.

Mythic heads, goddesses, garlands, and griffins—Antalya’s fragments pulse with ancient story

Pottery and glass are among the first artifacts you encounter. Rows of delicate amphorae, jugs, and flasks line the displays—some glazed in rich umber, others in oceanic hues. These weren’t just utilitarian; they were expressive. Shapes varied by region and function, and often, their surfaces bore geometric patterns or figural scenes. The glass, delicate and luminous, ranges from aquamarine to amber, with vessels so fine they appear impossibly thin.

Painted myth and blown glass—evidence of daily life and divine imagination

Metalwork adds a different note—subtler, darker. There are tools and coins, yes, but also weaponry, jewelry, and ritual objects. Some are impossibly ornate. Others are worn smooth by touch and time. Bronze heads, helmets, and votive offerings stand as reminders of both warfare and worship.

Sculpture, of course, is the museum’s central language. Busts of Roman emperors, mythic gods, and funerary figures populate the halls. Some are missing noses or limbs, others are impeccably preserved. The marble seems to breathe. Folds of drapery curl like cloth. Hair tangles with weight. Muscles hold tension. Every figure carries an echo.

A selection of classical statues inside Antalya’s Archaeological Museum

Reliefs and friezes, carved into stone blocks and sarcophagus panels, present scenes of revelry, mourning, battle, and devotion. There’s dynamism here—a freeze-frame of motion. Figures twist, animals lunge, garments billow.

Fragments of reliefs depicting mythic beasts, divine figures, and narrative scenes—each stone a window into ancient cosmologies

Sarcophagi are their own universe. Monumental and intimate at once, they’re carved with mythological tableaux, heroic battles, and portraits of the dead. One room alone is filled with them, side by side like a marble necropolis. It’s almost too much. But also impossible to leave.

The sarcophagus gallery stuns with myth-laden marble, from reclining effigies to riotous Bacchic scenes carved in exquisite detail

Coins and iconography occupy a smaller upstairs gallery. They shimmer under dim lights, stamped with emperors’ profiles or deities’ insignia.

Alongside them, religious paintings and icons offer a later period of artistic and devotional life.

These feel more solemn, more enclosed. A shift from the open, public nature of the classical works below.

Peacocks and fragments

Beyond the museum’s grand halls and shadowed galleries, the outdoor section unfolds more slowly. Here, under the Mediterranean sun, history stretches its limbs.

In the museum’s garden, carved stone relics stretch across time

The grounds feel part sculpture garden, part storage yard, part secret park. Sarcophagi, fragments of friezes, torsos and pediments and carved masks rest among the trees like visitors in no rush to leave.

Some of the stones are tagged and labeled; others lean quietly against each other, weather-worn but expressive. The repetition of theatrical masks—many with hollow, almost gasping mouths—feels especially uncanny. You start to notice their variations: the furrowed brows, the wild curls, the deep-cut eyes. Their expressions verge on comic, tragic, stunned. They evoke not just performance, but the faces of myth itself—Dionysian revelry, Orphic sorrow, Medusan horror. They become a kind of open-air chorus, frozen mid-breath.

Open-mouthed masks and winged figures peer out from stone, dramatic echoes of ancient performance and myth

We passed columns, pediments, and friezes, resting in the sun. But perhaps the most unexpected part of the visit? The peacocks.

Peacocks—both dazzling blue-greens and rare whites—strut through the museum grounds

When we visited, several strolled the grounds: emerald-throated males dragging iridescent tails, a pair of ghostly white ones moving like apparitions. They moved between columns and cracked sculpture with an uncanniness that made them seem both ornamental and utterly at home. A living symbol of beauty among the beautiful ruined things.

There’s a subtle magic to this outdoor section. It’s not just an annex to the museum’s interior—it’s a continuation of it, where art and time are not preserved behind glass but breathing with the air. A place where you can sit on a bench beside a centuries-old sarcophagus, or watch a peacock preen beside a lion-headed column.

How to visit

Antalya’s Archaeological Museum is easily accessible by public transport. Simply take the tram heading west and ride it to its final stop—Müze. From there, it’s just across the street.

You’ll want a few hours, minimum. If you’re someone who likes to read every placard, you could spend half a day here.

The entrance fee is modest, and there’s a café nearby if you need a break between galleries.

Photography is allowed, but flash is not. And if you’re an artist, consider bringing a sketchpad—this is a place that rewards close observation.