Long before Chiapas was a dot on our map, the Zapatista movement had already entered our consciousness (primarily thanks to this book by Arturo Escobar) as one of the most compelling demonstrations that communities can build futures outside the logics of coloniality and capitalist modernity.

Caracoles, the autonomous Zapatista self-governing regions, function as political, cultural, and pedagogical centers. They are the heart of Zapatista civil organization: slow, spiral-shaped constellations where decisions are made collectively, where communities govern themselves, and where the connection between land, dignity, and autonomy becomes visible in daily life.

The word caracol means snail, and the metaphor is intentional. In Zapatista cosmology, the spiral is both movement and memory: a way of advancing that requires circling back, listening inward, and grounding action in collective history.

Each Caracol has its own Junta de Buen Gobierno (Good Government Council), composed of rotating community-elected authorities. These are not leaders in the hierarchical sense; they are caretakers of collective will, seated there through service, not power. The Caracoles are where disputes are resolved, resources are organized, and community relationships are tended. They hold schools, clinics, cooperatives, workshops, archives, and ceremonial spaces. They are living infrastructures of Indigenous autonomy.

Our initial desire was to visit Oventic, one of the Zapatista Carcacoles in Chiapas. When we learned that it was closed to visitors during our time in San Cristóbal de las Casas, we instead looked toward CIDECI (Centro Indígena de Capacitación Integral / An Indigenous Center for Integral Learning), Universidad de la Tierra (University of the Earth).

CIDECI is not a Caracol. It is not governed through the same assemblies. But it breathes in the same ideological air: autonomy, interdependence, dignity, and education as a communal right. It stands adjacent to the Zapatista struggle, an ally and participant in the broader ecosystem of Indigenous self-determination.

Before sharing about our own experience visiting CIDECI, we'd like to share an excerpt from Tom Murray's account of visiting Oventic, as we think it beautifully situates Zapatista politics:

One sunny day we are taken across a river and to the top of a nearby mountain ridge where we sit in a circle in the shade of the pine trees. Efrain lays out seven cards each stating a Zapatista organizing principle. He emphasizes that these are not a model to be applied but more like ‘guides’ that emerge from the indigenous way of seeing and living. These are:

To propose, not to impose

To represent, not to supplant

To lower, not to elevate oneself

To serve, not to serve oneself

To obey, not to command

To convince, not to win

To create, not to destroy

The Zapatistas share a broad understanding of what it means to be anti-capitalist. In the Sexta Declaration, they side with the ‘humble and simple people’ of the world who are looking and struggling against and beyond neoliberalism, seeking dignity. Efrain says that an indigenous word ‘chulel’ captures the living quality of life, all the life force or energy involved in the earth, in one’s own life, even the potentialities latent in objects and things. Capitalism is a destroyer of ‘chulel’, of nature and of community. It promotes an extreme individualization and dehumanization. The Zapatistas are on a path or a way of true living, emerging out of and realizing chulel.

And further to that, a quote from Comandanta Hortensia, a leader within the Zapatista movement, that foregrounds their political efforts against neoliberalism:

"The world is very big and all of us fit, all of us. The only thing that does not fit is the capitalist system because it dominates everything and doesn't even let us breathe. Worst of all is that capitalism has no end – no death, destruction, misery or desolation is enough. No, it wants more: more war, more death, more destruction."

The world does not offer many places where cosmology, pedagogy, craft, healthcare, and politics flow together in one coherent, autonomous rhythm. The Zapatista movement in Chiapas emerged precisely to protect this coherence, a coherence violently disrupted by centuries of colonialism, land dispossession, state neglect, and the forced imposition of a single worldview.

When the Zapatistas rose publicly in 1994, it was not a call for power as defined by the state. It was a call for dignity, for Indigenous self-determination, and for the right to craft a future rooted in their own cosmologies. For many, this was the first time Mexico, and the world, saw an Indigenous-led uprising articulate not just resistance, but an entirely different horizon of possibility.

At its heart, the Zapatista movement is a project of autonomy. Not isolation, not separatism, but a reorientation around community-led governance, shared land stewardship, and social systems organized through collective decision-making. The Zapatistas built their own autonomous municipalities, their own schools grounded in decolonial education, their own healthcare networks, and their own cooperative economies. These weren’t utopian fantasies. They were practical infrastructures designed to sustain life outside the extractive logic of the Mexican state and global capitalism.

The Zapatista philosophy holds that liberation must be lived, not declared. This means the work of autonomy is daily, material, and relational: farming collectively, preserving Indigenous languages, revitalizing ancestral knowledges, and crafting schools that teach from within local cosmologies. It is a politics that lives in bodies and fields, not only in books.

What makes the Zapatista movement so compelling, even beyond Chiapas, is that it does not imagine “the future” as a singular path. Instead, it embraces pluriversality, a worldview that welcomes many futures, many knowledges, and many forms of life. This stands in direct opposition to the universalizing, homogenizing narrative of Western modernity, which presumes that all societies must follow the same developmental arc. In the Zapatista imagination, diversity is not something to be tolerated; it is the foundation of freedom. This is why their rallying cry, “a world where many worlds fit,” has echoed far beyond Mexico and into global movements for climate justice, Indigenous sovereignty, and anti-capitalist organizing.

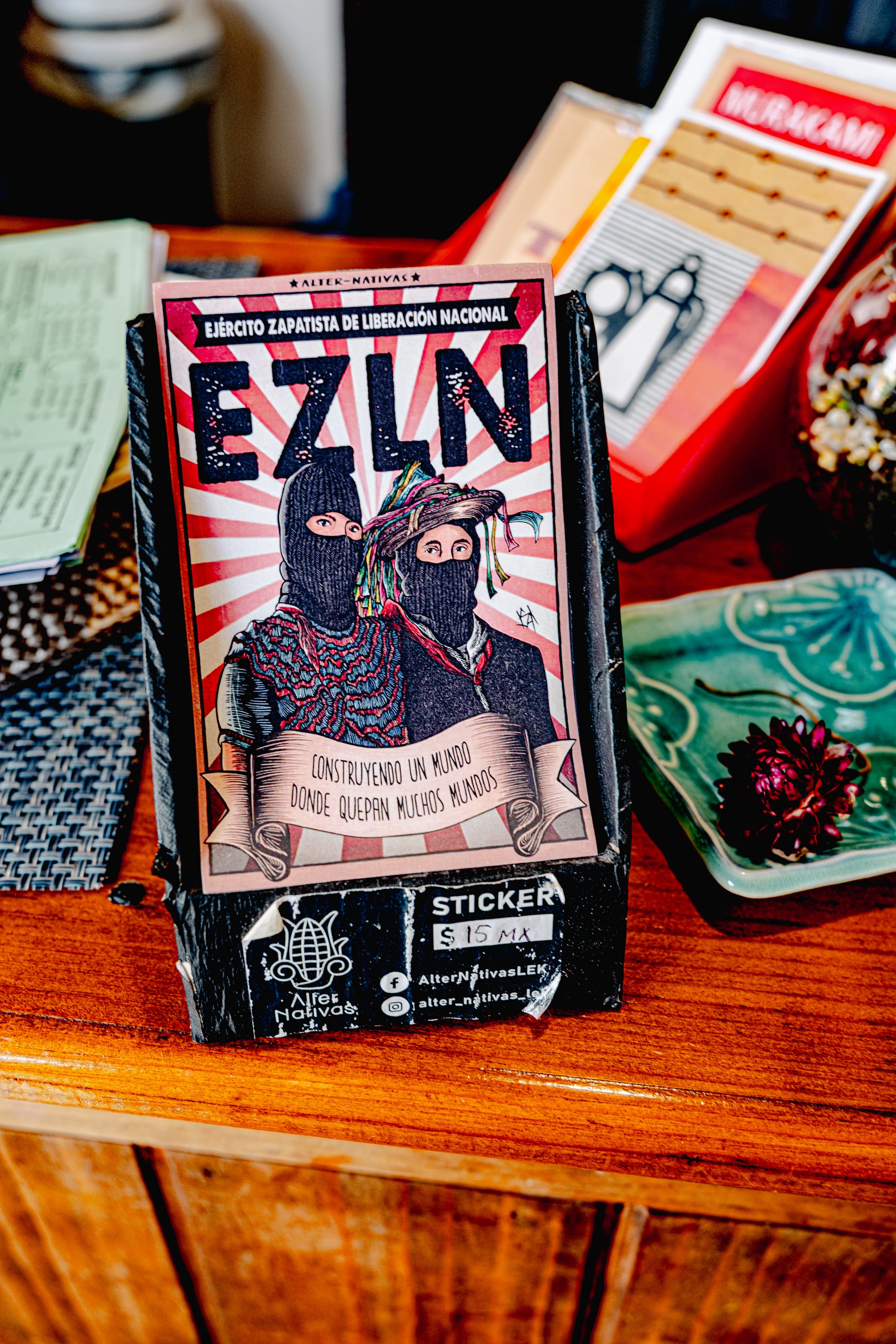

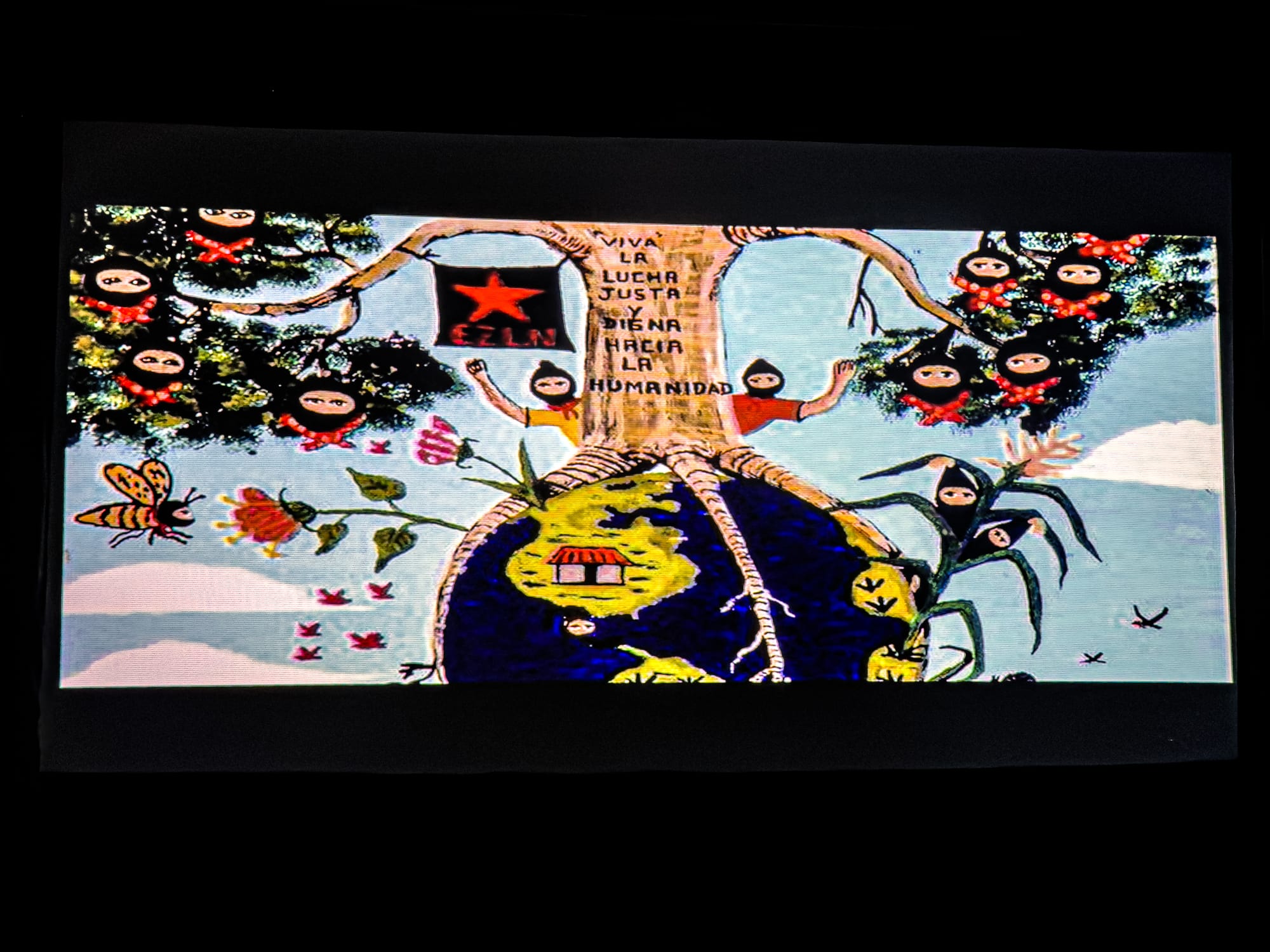

Zapatista-themed artwork and merchandise, featuring EZLN stickers, feminist and indigenous resistance illustrations

For anyone learning about Zapatista history, it’s important to remember that their struggle is not metaphorical. It is grounded in land, labor, territory, and survival. The ability to farm one’s own corn. To teach one’s own children. To make decisions in one’s own assembly. These are not abstract rights—they are the conditions for life itself. And because of that, the Zapatistas have remained committed to autonomy even as global attention rises and falls.

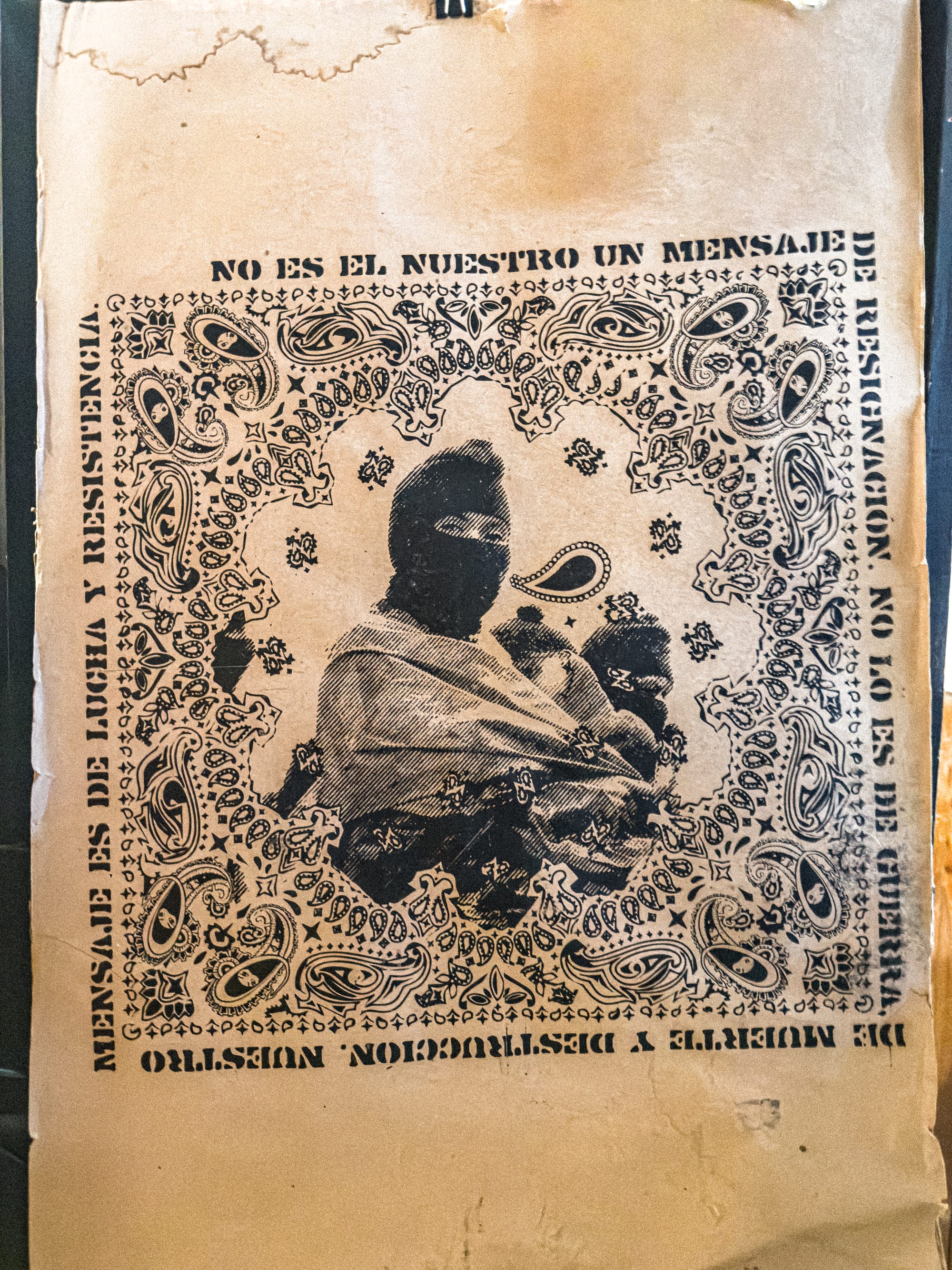

Archival-style Zapatista artwork paired with locally grown heirloom corn

Their communities continue to farm, educate, care, build, govern, and imagine outside the gaze of the state, often despite immense material challenges. They are not waiting for permission to craft a different world. They are already living inside one.

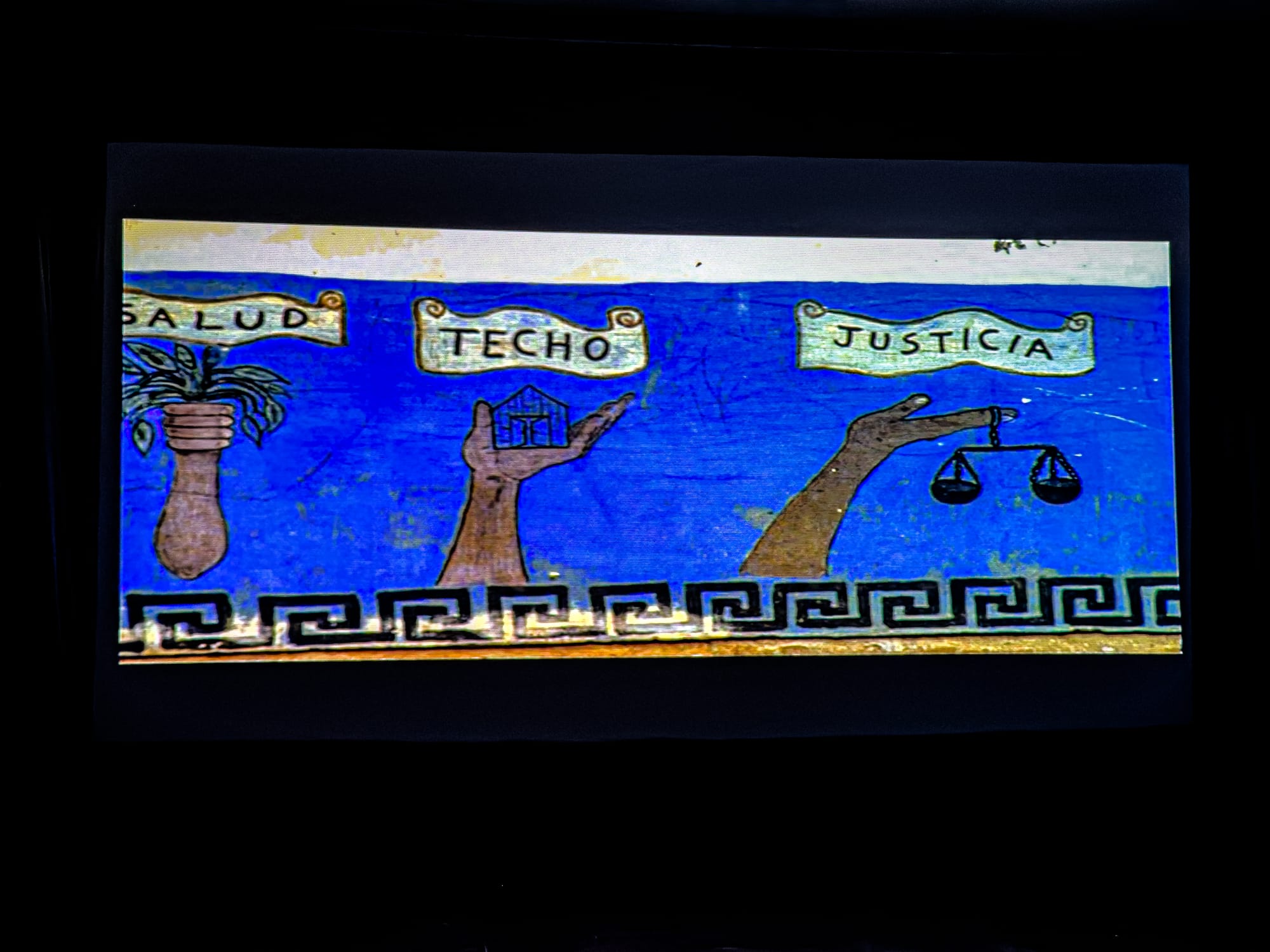

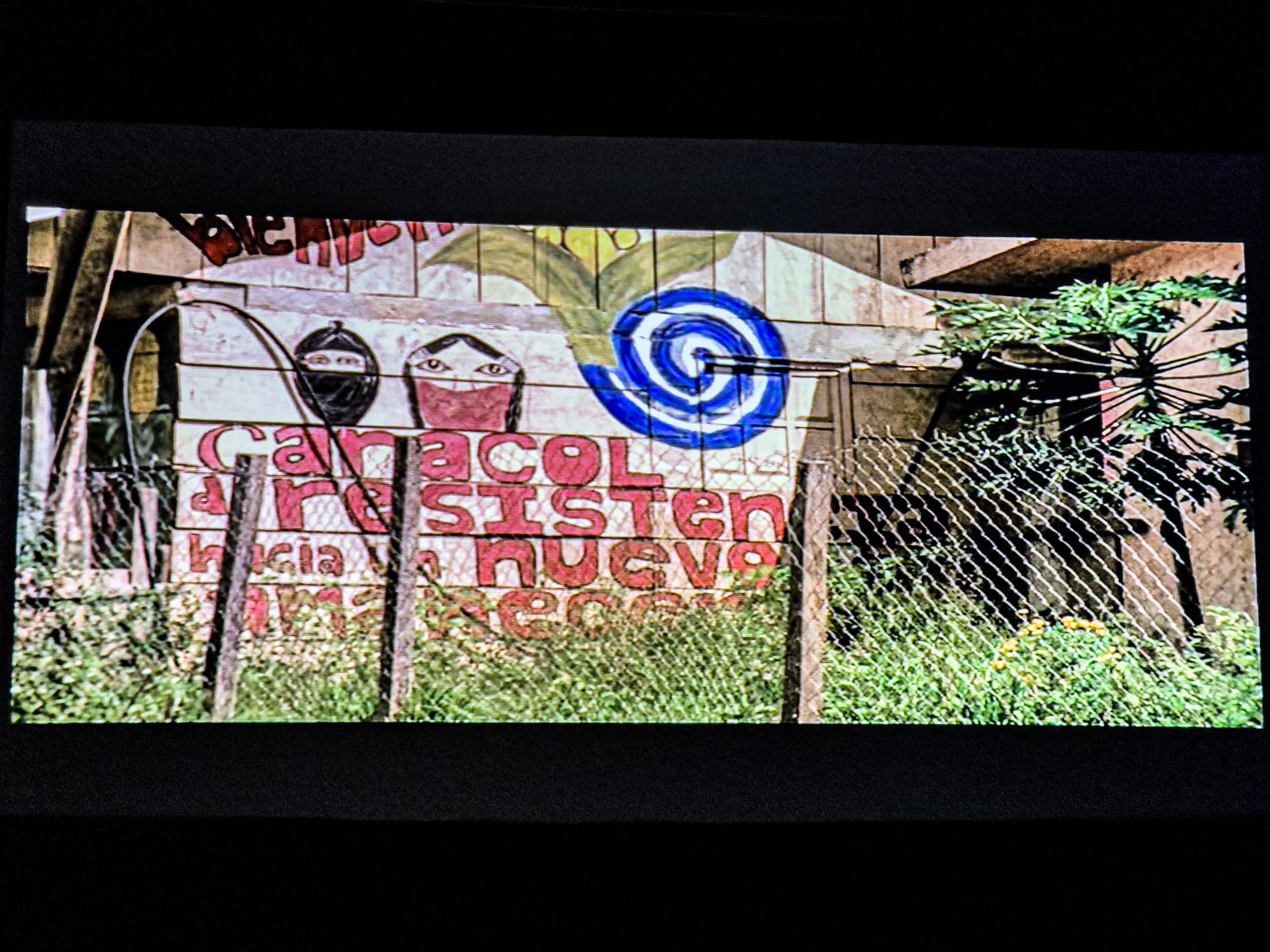

From Kinoki's screening of a Zapatista film

Arriving at CIDECI

To get to CIDECI, we took a colectivo (a shared transportation bus) to the very end of its route, then walked a bit along a dirt path until we reached its location.

Murals and banners outside CIDECI, featuring imagery of Indigenous motherhood and resistance

The first thing we noticed wasn’t the architecture or the layout but the murals—hundreds of them, layered across walls, doorways, storage buildings, workshop facades. Murals of maize, mountains, masked figures, jaguars, grandmothers, rebels, seeds, and spirals. Each one a worldview painted in color. Each one carrying the philosophy that land is not property, that knowledge is communal, that liberation is collective, and that people are made through relation.

Corn was everywhere—not as an aesthetic, but as ontology. According to many Indigenous cosmologies in the region, we are made of corn; corn is ancestor, teacher, and sustenance.

Corn, symbolic of Indigenous identity, land, and resistance in Chiapas

Upon asking some folks living at CIDECI if we could get a guided tour, we were taken to a little house near the back perimeter, where we then waited outside to meet "the doctor."

The doctor is an actual doctor, and before greeting us, he was with a community member who was feeling unwell that day. When he finished his consultation, he welcomed us into a beautiful room adorned with art and natural objects.

Vibrant folk art, ceramics, and plants surround the table where we spoke with the doctor

We spoke to him in Spanish, stating our names and why we were interested in visiting CIDECI.

He explained to us about CIDECI's purpose and history, and we had some time to ask him questions.

Following our meeting with the doctor, we were handed off to another member of CIDECI who would then show us all around the many parts of the community.

Walking around CIDECI: autonomy in practice

CIDECI is not designed for spectators, which is precisely why the experience carried so much weight. Every space we walked through was purposeful, lived-in, and in motion.

The school

Our first stop was a school building. Our guide explained, in his quiet way, that students here learn Zapatista history, political formation, and the principles of autonomy.

Scenes from the learning areas of CIDECI-UniTierra

Here, Zapatista philosophy is not a subject—it is a practice. Students learn the history of Indigenous resistance not as distant memory but as lineage.

Small details reflect a blend of autonomy, art, and community-based learning

They study communal work not as volunteerism but as the backbone of political life. Their education begins with the land and extends into the social fabric.

The infirmary

Next, we were led to the infirmary, a small building marked by herbal motifs.

This was not a place fetishizing “natural medicine”; it was a place that had no need for the distinction. For the people who live here, plants and remedies are not alternatives to Western healthcare—they are the original system, the one that never relied on pharmaceutical markets or state funding.

People are treated using both biomedical and herbal approaches, depending on need. There is a quiet pragmatism: use what heals, discard what harms, share what works. In a world where healthcare is increasingly commodified, the simplicity of this ethic felt radical.

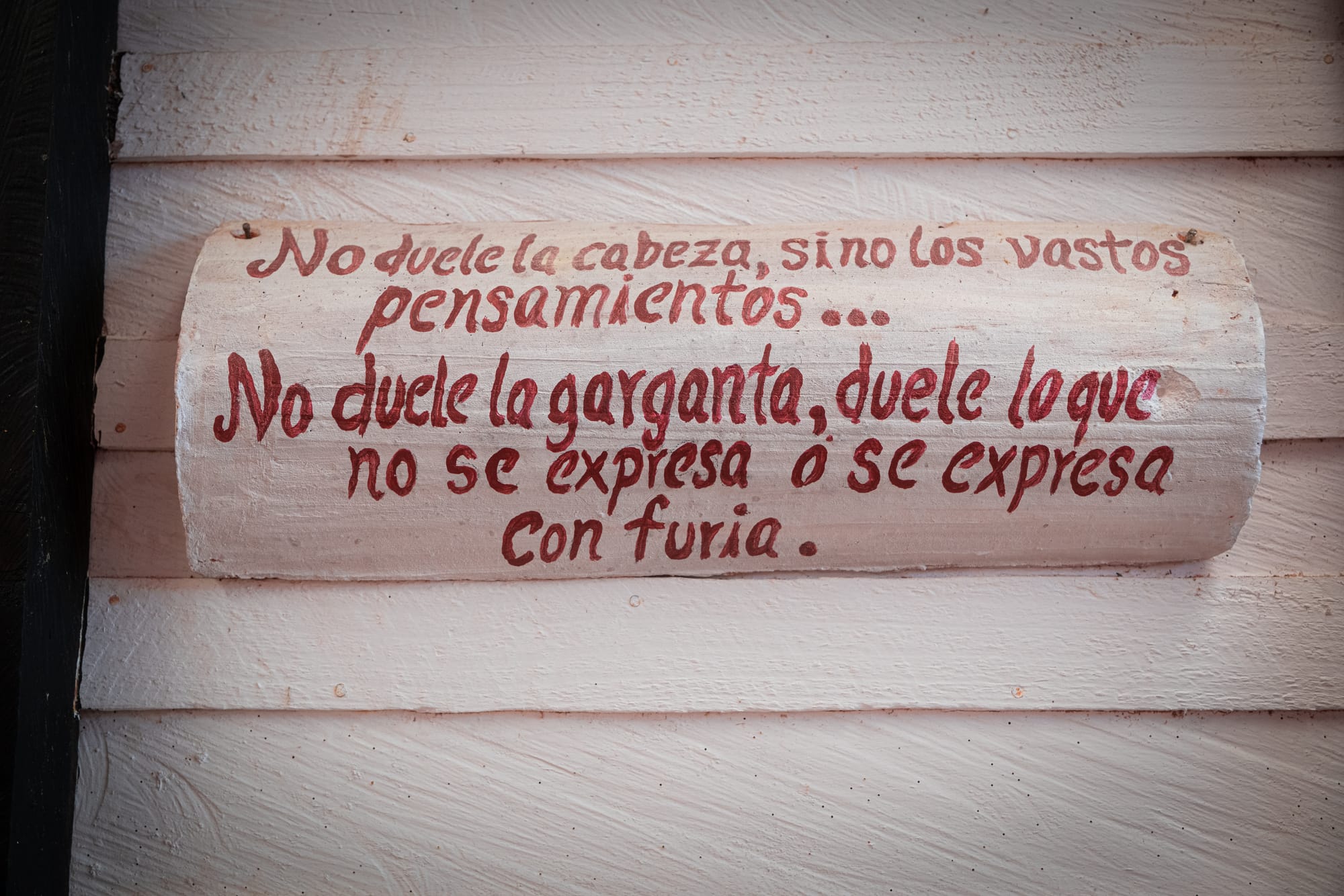

“It is not the head that hurts, but the vast thoughts…

It is not the throat that hurts — it is what goes unexpressed, or what is expressed with fury.”

Herbal medicine here does not gesture toward nostalgia or “tradition” as branding. It is woven into the community’s self-determination: a medical autonomy that resists dependence on fragile supply chains and neoliberal austerity. The infirmary embodies a politics of care—one that treats health as communal rather than individual, and relational rather than transactional.

Communal kitchens and gardens

Finally, we arrived at the kitchens—the warmest part of CIDECI in every sense. The smell of fresh bread found us before we even stepped inside. Within, people were kneading dough, washing vegetables, stirring pots of beans, preparing meals for dozens. Some chatted softly, others worked in near silence, all moving with the unselfconscious ease of those who understand that nourishment is a form of governance, and that the health of the community is built three times a day, in shared labor.

Communal kitchen areas

Food here is a shared rhythm that structures the day, a material expression of autonomy. To feed one another is to affirm that the community survives because the community cares.

Just beyond the kitchen walls stretched the gardens—patches of green organized not by aesthetic landscaping but by utility, season, and soil. Rows of herbs, greens, corn, and medicinal plants grew in quiet abundance. The produce wasn’t enough to supply the entire community every day, but it covered a meaningful portion of their needs and symbolized something deeper: CIDECI as an ecosystem capable of sustaining itself, at least partially, outside of the industrial agricultural machine. Here, tending the land is as essential as tending the classroom or the workshop. Food doesn’t arrive on trucks; it emerges through relationship—between soil, seeds, bodies, and time.

Vegetable beds in the agroecological gardens at CIDECI

CIDECI felt like its own small universe—one where education, healthcare, craft, and sustenance form a circular system rather than a set of isolated tasks. A world that does not need to rely entirely on outside agriculture to survive, and that refuses the dependency structures that neoliberal modernity imposes on rural communities.

The workshops: instrument-making, textile and clothing production, and art

From the gardens and kitchens, our guide led us into the workshops—the pulsing, hand-shaped heart of CIDECI. If the classrooms offered the intellectual grounding of autonomy, the workshops revealed its material logic. Here, knowledge lived not in abstraction but in fingertips, rhythm, repetition, and shared practice. This was where autonomy became tactile.

The first room we stepped into held instrument-making. The air smelled of sawdust and resin; curls of wood shavings spiraled across the floor like small, soft archives. One man sanded the curve of a guitar’s body with a concentration so steady it felt devotional. Watching him work, it was clear that instrument-making here wasn’t “craft” in the decorative sense. It was a form of thinking, a way of entering relationship with material, a daily practice of autonomy—tactile knowing in its purest form.

A space for crafting instruments at CIDECI

A few buildings over, the textile and clothing workshop opened into a different kind of quiet. Women sat at tables and looms, weaving garments with colors and patterns that carried cosmological significance—geometries of memory, lineage, and land. Each piece was a conversation between tradition and present need, between ancestral technique and contemporary autonomy. Clothing production here is not fashion; it is continuity. It preserves culture, resists homogenization, and asserts Indigenous presence in a world that continually tries to erase it. Every woven thread was a reminder that identity can be carried on the body, stitched in resistance, worn as sovereignty.

Clothing and textile workshops at CIDECI

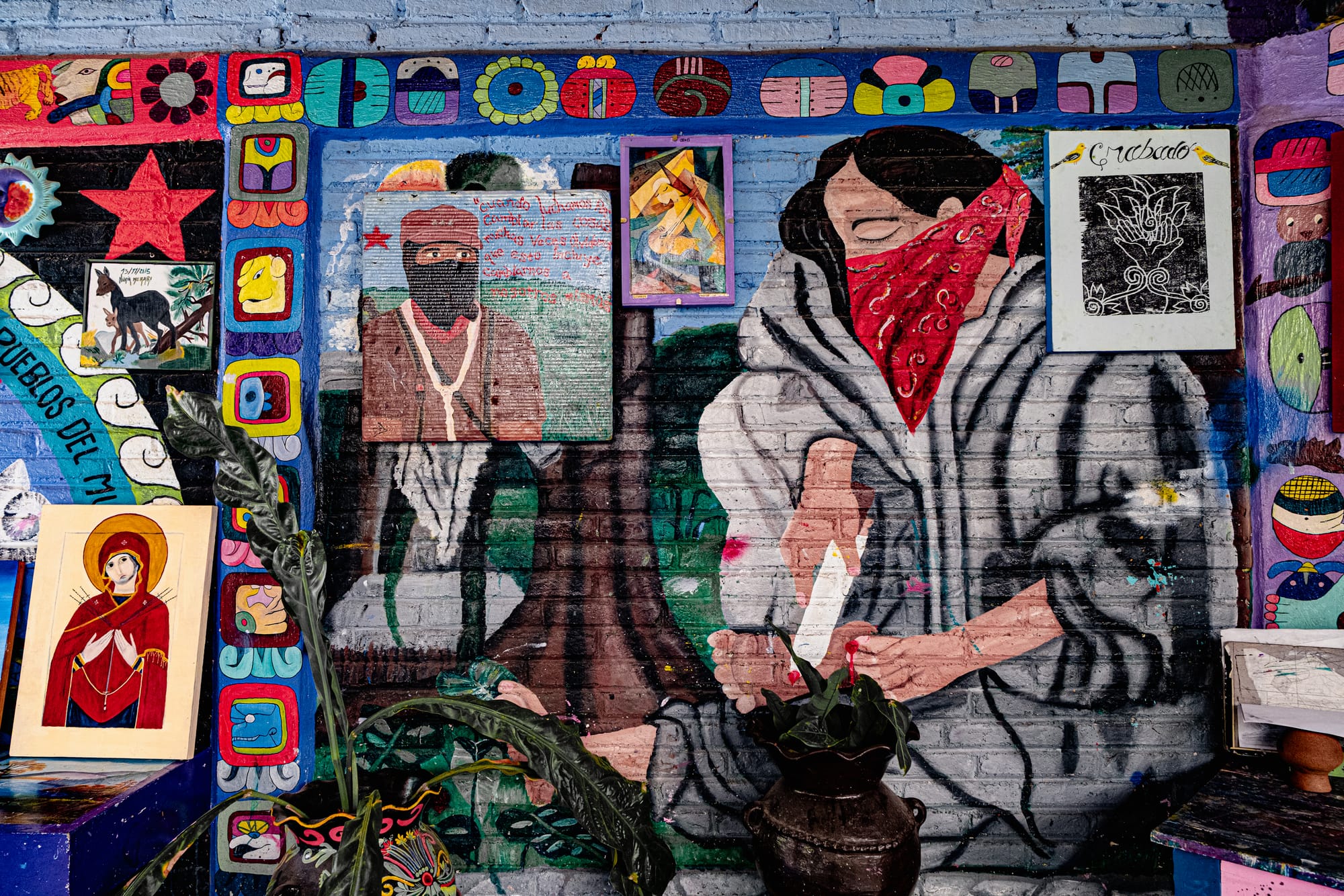

Further along, we entered a space buzzing with paint, brushes, and murals. Art at CIDECI is unmistakably political, but never didactic. Murals here are not ornament. They are pedagogy—living walls that teach cosmology, history, and collective struggle.

A workshop at CIDECI, filled with murals, student drawings, painted furniture

Taken together, the workshops formed a constellation of practices that sustain the community in ways far deeper than economics. They offered the skills to repair, to build, to clothe, and to remember. In a society where most objects arrive through global supply chains and leave through landfill routes, CIDECI’s way of working felt almost insurgent: a commitment to learning what your hands can do, and to trusting that the future is something you craft rather than consume.

Paintings and murals at CIDECI

Walking between these spaces, we began to understand autonomy not as an ideology, but as a daily labor—manual, collective, imperfect, and deeply alive. Here, instrument-makers, weavers, and muralists were not specialists separated by trade; they were participants in the same ongoing experiment in self-determination. Every workshop was another part of the circulatory system that keeps CIDECI thriving.

Zapatista murals at CIDECI

The murals found throughout CIDECI-Unitierra form a living visual archive of Zapatista thought, expressing a philosophy that is simultaneously aesthetic, political, spiritual, and pedagogical. Rather than serving as passive decoration, they operate as active articulations of resistance, autonomy, and collective dignity. Their presence on walls, walkways, classrooms, and communal spaces signals that learning is not confined to books or formal lessons; it permeates the built environment itself. The imagery that recurs across these murals reflects the core values of the Zapatista movement—self-determination, communal labor, Indigenous identity, anti-capitalist critique, and the vision of a world where many worlds fit.

A consistent theme is the representation of Indigenous life as foundational to resistance, portrayed not as a relic of the past but as a vibrant, living force. The murals often embed imagery of corn, weaving, local flora, and the tools of communal labor. These motifs function as reminders of the deep cultural continuities that sustain Zapatista autonomy.

Murals at CIDECI celebrating intergenerational care and community memory

Corn, for example, stands not only as a staple crop but as a symbol of Indigenous survival and self-sufficiency. Likewise, woven patterns and textiles evoke centuries-old traditions of handiwork that merge utility with beauty, and which carry within them stories of lineage and territory. In the murals, these elements are not nostalgic; they are political affirmations of identity as a site of strength in the face of homogenizing global pressures.

Corn, community, and Indigenous identity appear throughout CIDECI's murals

Collective labor is celebrated, depicted through figures engaged in farming, building, teaching, or gathering in assembly. The emphasis on shared work reflects the Zapatista concept that autonomy is not granted or inherited but produced daily through cooperation. These images visually reinforce the idea that communities build their own futures—not only physically, through the construction of schools, clinics, and cooperatives, but socially and intellectually, through shared decision-making and the creation of deep mutual support networks. In this sense, the murals act as mirrors reminding viewers that autonomy is a practice, not a slogan, and that it requires constant, participatory engagement.

Equally central are concepts of rebellion and critical consciousness. Many murals incorporate symbolic representations of refusal, awakening, or confrontation with imposed systems of power. The figures often gaze outward or stand with postures suggesting alertness, readiness, or vigilance. These artistic cues speak to a broader Zapatista insistence on the “dignified rage” necessary to challenge exploitation. The murals do not depict violence or aggression but instead highlight clarity of vision and moral resistance: the act of seeing the world as it is, recognizing oppression, and choosing to respond collectively. This reflective and conscious form of rebellion aligns closely with Zapatista discourse, which foregrounds critical thought and community deliberation as tools of struggle.

Symbolic figures

A common recurrence in these visual narratives is the land itself, represented as both home and subject. Mountains, valleys, rivers, and forests appear in stylized forms, often intertwined with human figures or framed as protective presences. The land is not portrayed as scenery but as a central protagonist, an active participant in the community’s life and autonomy. This reflects the Zapatista understanding of territory not merely as physical space but as a relational system encompassing spirituality, ecology, memory, and responsibility. The murals remind observers that defense of land is inseparable from defense of culture, and that both are essential for constructing alternative modes of living outside extractive frameworks.

Murals in learning spaces frequently integrate symbols associated with knowledge—books, pencils, candles, pathways, seeds, and eyes. These elements suggest that learning is illumination, germination, growth, and collective vision. In the Zapatista worldview, education is not a method for inserting information but a means for cultivating the capacity to think critically, to speak one’s own history, and to transform one’s community. The murals thus function as pedagogical tools, visually reinforcing the idea that knowledge is inseparable from autonomy. They insist that learning is not passive reception but an emancipatory process that unfolds through dialogue, observation, and self-directed exploration.

Closely linked are the concepts of plurality and coexistence. Many murals employ patterns, colors, or geometric arrangements that suggest diversity held together by harmony. Figures appear in groups rather than individually, emphasizing community over individualism. Distinct visual elements coexist without domination or hierarchy, echoing the movement’s famous articulation of “a world where many worlds fit.” This message is not abstract; it reflects the concrete sociopolitical project of building governance structures that recognize multiplicity of languages, cultures, and ways of being. The murals teach an ethics of respect, cooperation, and non-hierarchical community life simply through the way shapes and colors inhabit space together.

A further motif, subtle but significant, is the representation of time—cycles, seasons, or symbolic markers that evoke continuity. Spirals, suns, moons, or sequences of growth appear often, reminding viewers that political transformation is long-term work rooted in generational persistence. This contrasts sharply with the accelerated tempo of capitalist modernity. The murals convey a slower, cyclical understanding of change, one that acknowledges both patience and the inevitability of renewal. By embedding temporal rhythms into the walls, the space encourages inhabitants to view their struggles and dreams not as isolated moments but as long arcs of collective becoming.

Vibrant geometric designs and floral motifs

Many murals also embody a sense of hope and world-building. Even when addressing themes of resistance or injustice, the imagery leans toward affirmation rather than despair. Eyes look toward horizons, pathways extend into open landscapes, and symbols of growth—sprouts, stars, seeds—appear frequently. This orientation toward possibility reflects the Zapatista commitment not only to opposing destructive forces but to constructing new, liberated forms of life. The murals thus serve as invitations to imagine and enact different futures, turning the environment of CIDECI into a laboratory of alternative imagination.

Finally, there is often a clear connection between the spiritual and the political. While not overtly religious, the imagery conveys a reverence for life, community, and the natural world. Light, wind, animals, and elemental forms are invoked to suggest that autonomy is not merely political organization but an ethical relationship with existence itself. This worldview challenges Western dualisms that separate nature from culture, politics from spirituality, or education from lived experience. The murals embody a holistic cosmology that underpins Zapatista practice, reminding viewers that liberation is as much about restoring relationships as it is about dismantling oppressive structures.

Nature-themed murals at CIDECI

Taken together, the murals at CIDECI form an immersive visual ecosystem of Zapatista meaning. They transform walls into a shared language through which autonomy, dignity, collective labor, ancestral knowledge, ecological respect, and radical hope are continuously expressed. Seeing them was, in all regards, a very beautiful experience.

A world where many worlds fit

In a global landscape shaped by neoliberal capitalism, extractive development, and the myth that Western modernity is the only viable future, CIDECI stands as a living reminder that other systems—other cosmologies, other pedagogies, other political rhythms—are not only imaginable, but already in practice.

Colorful CIDECI buildings and a playful poster

The Zapatista movement has long resisted the homogenizing force of the state and its colonial legacy. Their project is not merely oppositional; it is profoundly decolonial, rooted in Indigenous ways of knowing that predate the nation-state and refuse the economic scripts imposed by neoliberal reforms. CIDECI reflects this philosophy through its everyday life: education that resists credentialism, craft that resists industrialization, governance that resists hierarchy, and healthcare that resists the reduction of the body to a commodity.

Colorful details around CIDECI

What stayed with us long after leaving CIDECI was not a singular insight, but a shift in perception—a loosening of the default assumptions we carry about how a society must be organized and what forms of life are possible within (or beyond) the state.

What we encountered at CIDECI was not a romantic alternative, but a disciplined one. Autonomy here is built through kitchens and gardens, workshops and assemblies, shared labor and shared meaning. It is maintained through daily practices of care, responsibility, and collective governance.

Colorful gates painted with flowers and masked figures, alongside a striking portrait of a child

We left thinking about how much of our own lives unfold within infrastructures we did not choose—political, economic, technological—and how rarely we question their inevitability. CIDECI reminded us that inevitability is one of capitalism’s most successful illusions. Standing in the gardens, or inside the guitar workshop, or in front of a mural documenting centuries of Indigenous resistance, we felt the weight of that illusion fall away long enough to glimpse a truth the Zapatistas have articulated for decades: that there are many worlds already living beneath the surface of this one.

Murals at CIDECI celebrating autonomy and collective life

The question is not whether alternatives exist. The question is whether we are willing to recognize them, learn from them without appropriating them, and let them unsettle the narratives we’ve inherited about progress, development, and possibility.

Further information on CIDECI

What is CIDECI-UniTierra?

CIDECI (Centro Indígena de Capacitación Integral) is an autonomous learning community on the outskirts of San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas. It offers free, non-institutional education rooted in Zapatista principles of autonomy, dignity, and communal learning. It’s not a traditional university—there are no degrees, grades, or formal classes as you’d find in mainstream institutions.

Is CIDECI part of the Zapatista movement?

CIDECI is not a Zapatista Caracol, but it is deeply aligned with Zapatista principles and often hosts Zapatista cultural and political events. It’s a space of learning and dialogue where Zapatistas and supporters frequently meet.

Can visitors go to CIDECI?

Yes. The space is generally open to respectful visitors during the day. Prior to visiting, we would advise informing yourself about the Zapatista movement.

Is there an entrance fee or need for permission?

There is no entrance fee, and day visitors typically don’t need prior permission.

How do you get to CIDECI from San Cristóbal de las Casas?

CIDECI is located along the Periférico Oriente, on the southeastern edge of San Cristóbal. We recommend taking a colectivo.

Do you need to be a Zapatista to visit?

No, but you do need to be respectful of the space, the people who live there, and the political ethos. It is not a neutral cultural center—it’s an autonomous project rooted in Indigenous struggle and anti-capitalist philosophy.

Are the murals open to the public?

Yes. The murals are part of CIDECI’s environment, along walkways and buildings. Visitors often come specifically to observe them. Photographing murals is generally fine; photographing people requires permission.

Why are murals so important here?

Murals serve as visual education: they’re teaching tools, historical memory, and artistic expressions of autonomy. They convey Zapatista values—collective work, Indigenous identity, resistance, plurality, and dignity—without requiring written explanation.

Do I need to speak Spanish to visit?

It helps. Many signs, workshops, and conversations happen in Spanish or Tsotsil/Tseltal. For a simple visit or walk-through, Spanish isn’t strictly necessary, but engaging meaningfully is much easier with basic Spanish skills.

How does CIDECI sustain itself financially?

Through communal labor, donations, solidarity networks, and cooperatively produced goods such as textiles, crafts, or food. There is no tuition and no corporate or government funding.

Why do you recommend visiting?

CIDECI offers a rare chance to encounter a living experiment in autonomy, education, and community outside of conventional institutions. It’s a place where ideas about collective life, Indigenous knowledge, mutual aid, and alternative learning are not just discussed but practiced daily. Walking through the space—its murals, workshops, and gardens—gives visitors a grounded sense of what Zapatista principles look like in action. It’s not tourist attraction or "thing to do," but an opportunity to learn respectfully from a community building a different way of being in the world.