Across all our travels, few experiences have settled into us as deeply as Día de Muertos.

Not because it was visually striking, though it often is, but because it offered a fundamentally different relationship with death than the one we were raised with. Experiencing Day of the Dead in San Cristóbal de las Casas, where it is known to be especially spiritual, was deeply moving.

This post focuses on how Día de Muertos unfolded within the town itself: the altars, the streets, the shared moments, and the evening parade that brought color and movement to the city. Alongside this, we also visited three very different cemeteries during the celebrations—Romerillo, Zinacantán, and San Cristóbal’s Municipal Pantheon—each offering its own distinct expression of remembrance and ritual. Those experiences deserve space of their own, and we’ve written about them separately.

What Día de Muertos means in Chiapas

Día de Muertos—also called Día de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead—is often misunderstood from afar as a single, uniform celebration. In reality, it is a layered, regionally distinct constellation of practices that stretches across Mexico, shaped by Indigenous cosmologies, colonial histories, and local relationships to death, land, and ancestry.

At its core, Día de Muertos is not a celebration of death, but a ritual of relationship with it.

Long before Spanish colonization, many Indigenous cultures across what is now Mexico held cyclical understandings of life and death. Among Maya-descended communities—particularly relevant in Chiapas—death was not seen as an absolute rupture, but as a transition within a continuous moral and spiritual landscape. The dead remained present: as ancestors, guides, and witnesses.

When Catholicism arrived, these pre-Hispanic cosmologies did not disappear. Instead, they interwove with Christian calendars—most notably All Saints’ Day (November 1st) and All Souls’ Day (November 2nd)—giving rise to what we now recognize as Día de Muertos. But the synthesis was never total. In many regions, especially in southern Mexico, Indigenous logics still quietly lead.

In Chiapas, Día de Muertos often carries a distinctly spiritual and familial orientation. The focus leans less toward spectacle and more toward continuity: tending graves, preparing food for both the living and the dead, and lighting candles that mark presence. Altars (ofrendas) are not decorative centerpieces so much as temporary homes—thresholds where memory, nourishment, and prayer converge.

Marigolds, believed to guide spirits with their color and scent, appear everywhere. Food is prepared with care, not as symbolism alone, but as sustenance meant to be shared across worlds. Time slows. Homes and cemeteries become the primary sites of ritual, even as public spaces participate quietly.

In places like San Cristóbal de las Casas—where Indigenous Tsotsil and Tseltal traditions live alongside colonial architecture and contemporary life—Día de Muertos unfolds as something intimate yet collective. It is about maintenance: maintaining bonds, names, obligations, and care across generations.

To witness Día de Muertos here is to understand it not as an event, but as a practice of remembering that the dead are not gone—they are simply elsewhere, and for a few days each year, invited close again.

Co404 celebrations

One of the most meaningful Día de Muertos experiences we had in San Cristóbal happened not in a public square, but at home.

A shared ofrenda created together at Co404

At Co404, our digital nomad coliving space, the days leading up to Day of the Dead were marked by quiet preparation rather than programming. The intention was not to recreate a tradition perfectly, but to participate in it respectfully, with openness and care.

Marigolds and candlelight

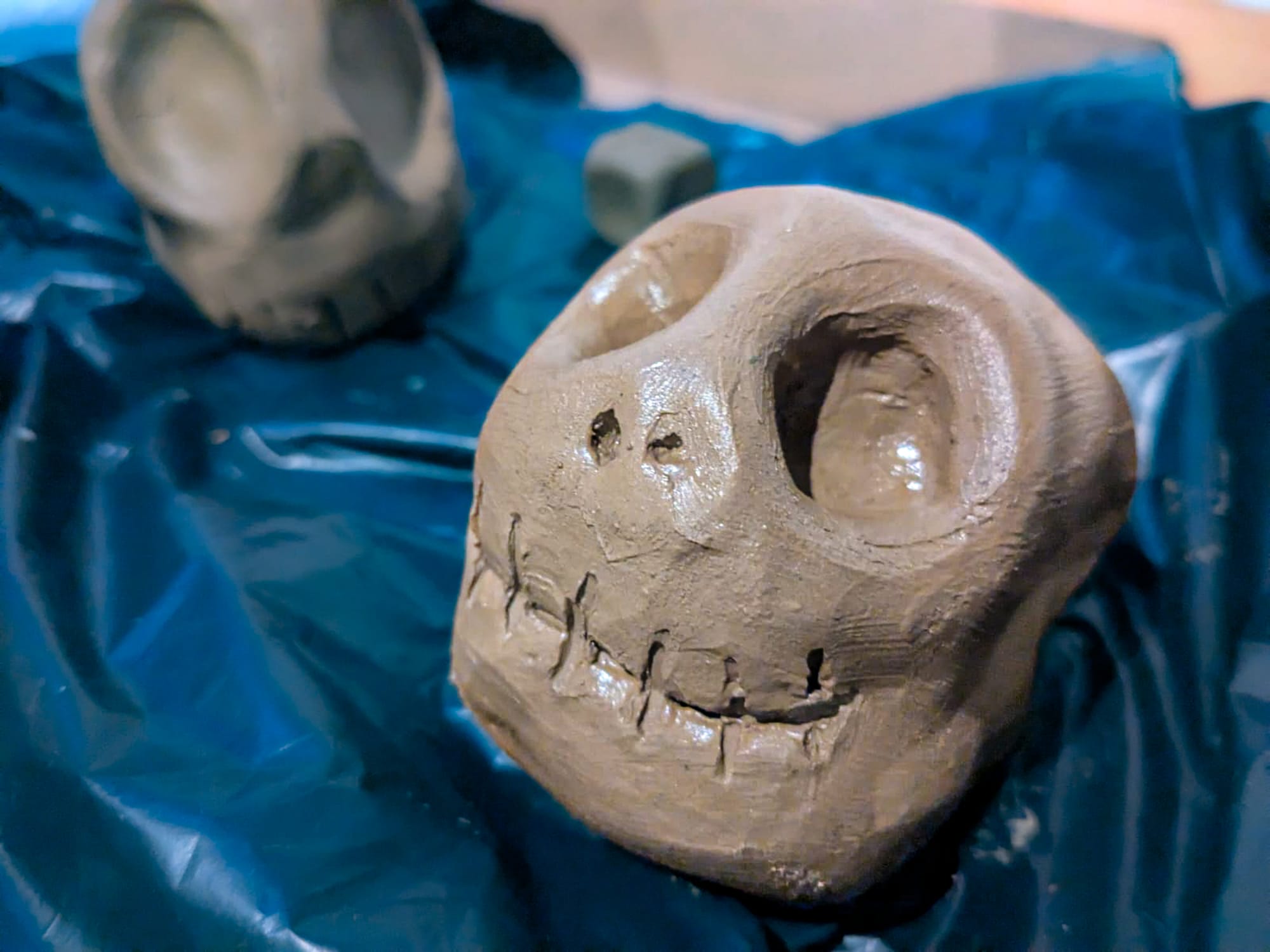

The first activity took place several days before Día de Muertos. As a group, we made clay skulls by hand, shaping each one slowly and imperfectly before setting them aside to dry. Later, we painted them—some carefully, some playfully—turning the process into a quiet, communal way of easing into the days ahead.

Painting clay skulls together ahead of Día de Muertos

Using the skulls, we later built an ofrenda, an altar to honor deceased loved ones. People brought photos, handwritten notes, small objects, flowers, food, and memories. Some offerings were deeply personal. Others were symbolic. Some honored grandparents or parents; others were for friends, ancestors, or figures whose presence still lingered in quieter ways.

Photographs and offerings arranged in quiet remembrance

The altar grew slowly, shaped by many hands and many stories.

Skulls, flowers, and candlelight on the ofrenda

Another evening, we watched the film Coco, as a shared reflection on memory, lineage, and the fragile work of keeping names alive.

Our coliving manager, Santi, later shared something that stayed with us: that Día de Muertos in San Cristóbal often carries a more spiritual, inward quality than in other parts of Mexico—less oriented toward grand displays, more toward prayer, remembrance, and presence. Whether or not that holds universally, it felt true in the way this space held the ritual.

Handmade details honoring memory and presence

On the morning of November 2nd, after the official Day of the Dead had passed, we gathered again, this time for a slow, communal brunch. Food was shared. Stories drifted. The altar remained nearby, quietly anchoring the room.

Sharing food together after Día de Muertos

There was no sense of closure, only continuation.

The city, decorated

Walking through San Cristóbal during Día de Muertos felt like moving through a living altar.

Ornate skeletons filling the plaza during Día de Muertos

The main plaza filled with ornate skeleton figures, each styled differently. Rather than feeling theatrical, they felt conversational, as if the boundary between worlds had thinned just enough to allow humor alongside reverence.

Floral Catrinas standing watch in the main plaza

Marigolds were everywhere. Lining streets. Framing doorways. Spilling out of buckets, stalls, and temporary altars. Their scent hung in the air—sweet, earthy, and unmistakable. In Mexican tradition, marigolds are believed to guide spirits back to the world of the living. Here, they seemed to guide the living too, slowing footsteps, drawing attention downward and inward.

A floral carpet and playful skeletons in the plaza

Cafés and restaurants across the city participated quietly. Small altars near counters. Candles tucked beside menus. Sugar skulls resting near espresso machines.

A public ofrenda layered with art, offerings, and marigolds

What stood out most was how integrated Día de Muertos felt into daily life. This wasn’t a pause from normal rhythms—it was an extension of them. People still worked, cooked, walked, and talked. But they did so with remembrance woven into the background, like a second layer of meaning.

Skeletons, papel picado, and marigolds animating the plaza

In the evenings, the city softened. Candlelight became more visible. The air cooled. Conversations lingered longer.

The parade

As evening fell on Día de Muertos, the energy in San Cristóbal shifted again—this time toward movement.

Music and dance carrying the parade through the night

The Day of the Dead parade unfolded through the city as a vibrant, communal expression of remembrance. People gathered along streets and sidewalks. Children, elders, families, and friends. Many dressed up. Many painted their faces—calaveras, Catrinas, and skulls adorned with flowers and symbols.

Elaborate costumes moving through the Día de Muertos parade

Earlier that day, Co404 had offered a face-painting activity for anyone who wanted to participate. It was a small gesture, but it mattered. Preparation felt collective. No one was watching from the outside—we were being gently invited in.

A moving altar carried through the streets at night

The parade itself was colorful and alive. Music, costumes, laughter, and solemnity all braided together.

Faces, flowers, and movement

What made it unforgettable wasn’t just the visuals, but the emotional texture. Joy and grief weren’t separated—they coexisted. People smiled while honoring the dead. They danced while remembering loss. It was a reminder that Día de Muertos is not about denying death, but about reintegrating it into life.

Horseback riders and costumes joining the night parade

Standing there, surrounded by faces painted in memory, we felt an overwhelming sense of gratitude—for being welcomed, and for witnessing something that wasn’t ours, yet wasn’t closed to us either.

Shared joy and connection along the parade route

Later, walking home through streets still scattered with petals and candle wax, it became clear why this experience would stay with us.

The cemetaries

We visited three cemeteries during the Day of the Dead celebrations: Romerillo, Zinacantán, and San Cristóbal’s Municipal Pantheon (which we also checked out prior to Day of the Dead as well). Each held a completely different expression of Día de Muertos, from intimate family vigils to larger communal gatherings. Those experiences deserve their own telling, and we’ve written about them separately.

Romerillo

Romerillo was our favorite of the three cemeteries we visited, and the one that felt the most distinctly local.

One of the most striking things about Romerillo is its location: it sits directly next to an amusement park. The contrast is jarring and unforgettable—rides and music on one side, families tending graves on the other. Celebration and remembrance happening simultaneously, without contradiction. It’s unlike anything we’d seen before.

Families tending graves together throughout the day

Inside the cemetery, nearly every grave was carefully decorated with pine needles, marigolds, fruit, candles, and offerings. Families gathered, talked, laughed, ate, and stayed for hours. It felt less like a place of mourning and more like a true celebration of the dead, held openly and without restraint.

If you were to visit just one cemetery during Día de Muertos in San Cristóbal, this would be the one. Romerillo is intense, beautiful, and unforgettable—a full expression of Day of the Dead in every sense.

Zinacantán

Zinacantán felt completely different from the other cemeteries we visited. As a town, Zinacantán is known for flower cultivation—one of its primary industries—and that shows unmistakably during Día de Muertos. Of the three cemeteries, this one was by far the most ornate, with graves absolutely covered in flowers of every kind.

Flowers across the cemetery hillside

When we visited, it was noticeably quieter than the others. That may have been due to timing, but we didn’t see large crowds or the same kind of ongoing celebration we experienced elsewhere. Instead, the atmosphere felt calmer and more contemplative, with fewer people moving through the cemetery at any one time.

The setting itself is part of what makes Zinacantán so striking. The cemetery sits on a hilltop, offering sweeping views of the surrounding landscape. Combined with the sheer abundance of flowers, it was visually stunning—less animated than Romerillo, but deeply beautiful in its own way.

San Cristóbal’s Municipal Pantheon

We actually visited San Cristóbal's Municipal Pantheon twice—once before Day of the Dead, and once during the celebrations.

Carrying flowers through the cemetery pathways

Despite being located right in San Cristóbal de las Casas, this cemetery felt less frequented by tourists than we expected. We’re not entirely sure why—perhaps because it’s so embedded in everyday city life—but it retained a very local atmosphere throughout.

Quiet moments of care inside the Municipal Pantheon

The Pantheon feels almost like a small town of its own. There are internal roads, vendors selling flowers, snacks, and drinks, and a steady flow of people moving through. Many of the graves are built like small houses, painted in bright colors and arranged in rows that resemble neighborhoods more than burial plots.

Music echoing through the cemetery as families gather

During Día de Muertos, families spent the entire day sitting by the graves. We saw live bands playing music, people eating together, talking, and lingering. It felt communal and unhurried—less visually ornate than Zinacantán, but deeply alive. An incredible experience, and one that felt very much rooted in the rhythms of the city itself.

A place we’d return to, without hesitation

We want to be clear about one thing: our experience of Día de Muertos is limited to San Cristóbal de las Casas. We can’t claim to have seen the celebrations across Mexico, and we can’t say, comparatively, that this is the place to experience Day of the Dead.

But we can say this: having experienced it here, we understand why some people travel to Mexico specifically for Día de Muertos. We met several people whose primary reason for coming was to witness these days. That wasn’t our intention—but after being present for it, it makes complete sense.

Day of the Dead woven into everyday city life

San Cristóbal feels like a particularly special place to experience Día de Muertos because of its quieter, more spiritual quality, and because of the strong Indigenous presence that continues to shape how remembrance is practiced in the region.

For us, these days became one of our most memorable travel experiences because they offered a way of relating to death that felt integrated, honest, and deeply human.

We would love to be back in San Cristóbal for Día de Muertos again someday. And while we’re sure the celebration takes many beautiful forms elsewhere, this is one we’ll carry with us—and return to, if we can.