Visiting Palenque was by far the most memorable experience we had in Chiapas.

If you only have room for one weekend trip from San Cristóbal de las Casas, this is the one we would recommend, without hesitation. The combination of distance, landscape change, historical depth, and sheer presence of the site makes Palenque feel fundamentally different from anything else in the region.

Stone terraces and shaded corridors invite slow wandering

We made this trip over a long weekend with friends from our digital nomad coliving space Co404, and paired our visit to the Palenque Mayan ruins with stops at Misol-Há and Roberto Barrios waterfalls. It’s worth noting upfront that Palenque fits naturally into a broader jungle itinerary rather than standing alone as a quick excursion.

While there are many tours that attempt to cover Palenque as a single-day trip from San Cristóbal, we strongly recommend staying overnight near the ruins. The journey is long, the climate shift is real, and the archaeological site itself is expansive. Giving it time changes the experience from something you merely see into something you actually absorb.

Collapsed walls and forest growth blur the line between architecture and landscape

For travelers who are short on time, there are organized day trips available. This popular day tour from San Cristóbal to Palenque with Misol-Ha is one of the more efficient options. But if your schedule allows, an overnight stay—or even two nights—will make the trip far more enjoyable.

For those who have the time, we'd recommend this 3-day tour from San Cristóbal to Palenque including Yaxchilán and Bonampak.

Getting from San Cristóbal de las Casas to Palenque

Palenque is located in northern Chiapas, deep in the lowland jungle, while San Cristóbal de las Casas sits high in the mountains. Although the distance doesn’t look extreme on a map, the drive is long and winding.

Travel time:

- By car or shuttle: ~5–6 hours (often longer with stops)

- By organized tour: usually 12–14 hours round-trip if done in one day

The route descends dramatically from the cool, pine-covered highlands into humid rainforest. Temperatures rise steadily, and the shift in climate is noticeable well before you arrive. This is one of the main reasons a day trip can feel exhausting—especially if you plan to walk the ruins properly.

Stone steps climb gradually into the jungle

If you’re traveling independently, leaving early in the morning is essential. Many people depart San Cristóbal around 4–5am when doing a day trip. For an overnight trip, leaving closer to 8–9am is much more humane and still allows you to arrive with daylight to spare.

We actually visited Misol-Há and Roberto Barrios waterfalls on our day of arrival, and saved the Palenque visit for the following morning, which meant we were able to arrive at opening time when there were less crowds.

Staying overnight in Palenque

Palenque is not a site you want to rush. The ruins themselves require at least two hours to explore at a comfortable pace, and that’s without accounting for heat, rest breaks, or curiosity-driven detours. Add the long drive on either side, and a same-day return becomes physically demanding.

Staying overnight near Palenque allows you to explore the ruins without time pressure, visit early in the morning before large tour groups arrive, better manage heat and humidity, and combine the trip with a visit to nearby waterfalls.

We spent one night near Palenque, which felt like the minimum. If you’re interested in extending the trip to more remote ruins like Yaxchilán and Bonampak, two nights or more are strongly recommended.

Palenque: jungle & ruins

Most accommodations are located either in the town of Palenque or along the road leading to the ruins. Given the jungle atmosphere, we strongly would advise looking for a place with air conditioning, as the humidity at night can be quite intense.

Our organized tour included a stay at a basic hostel, but if you're looking for a more private experience, we'd recommend checking out Hotel Mundo Maya Palenque, Hotel Chablis Palenque, or Hotel Boutique Quinta Chanabnal.

Historical context

Palenque, known in ancient times as Lakamha’, was one of the most important Maya city-states of the Classic period. Its name translates roughly to “Big Water,” a reference to the abundant springs and streams that run through the site.

The city reached its peak between 600–750 CE, during which time it became a major political and cultural center. Unlike some Maya cities built on flat plains, Palenque is embedded directly into the jungle-covered foothills of the Chiapas mountains, giving it a unique spatial relationship with water, forest, and terrain.

Water and stone quietly shape the experience here, with streams threading through the ruins and doorways framing light

One of the most significant figures associated with Palenque is K’inich Janaab’ Pakal, commonly known as Pakal the Great. He ascended to the throne at just 12 years old and ruled for nearly 70 years, overseeing an extraordinary period of architectural and artistic growth.

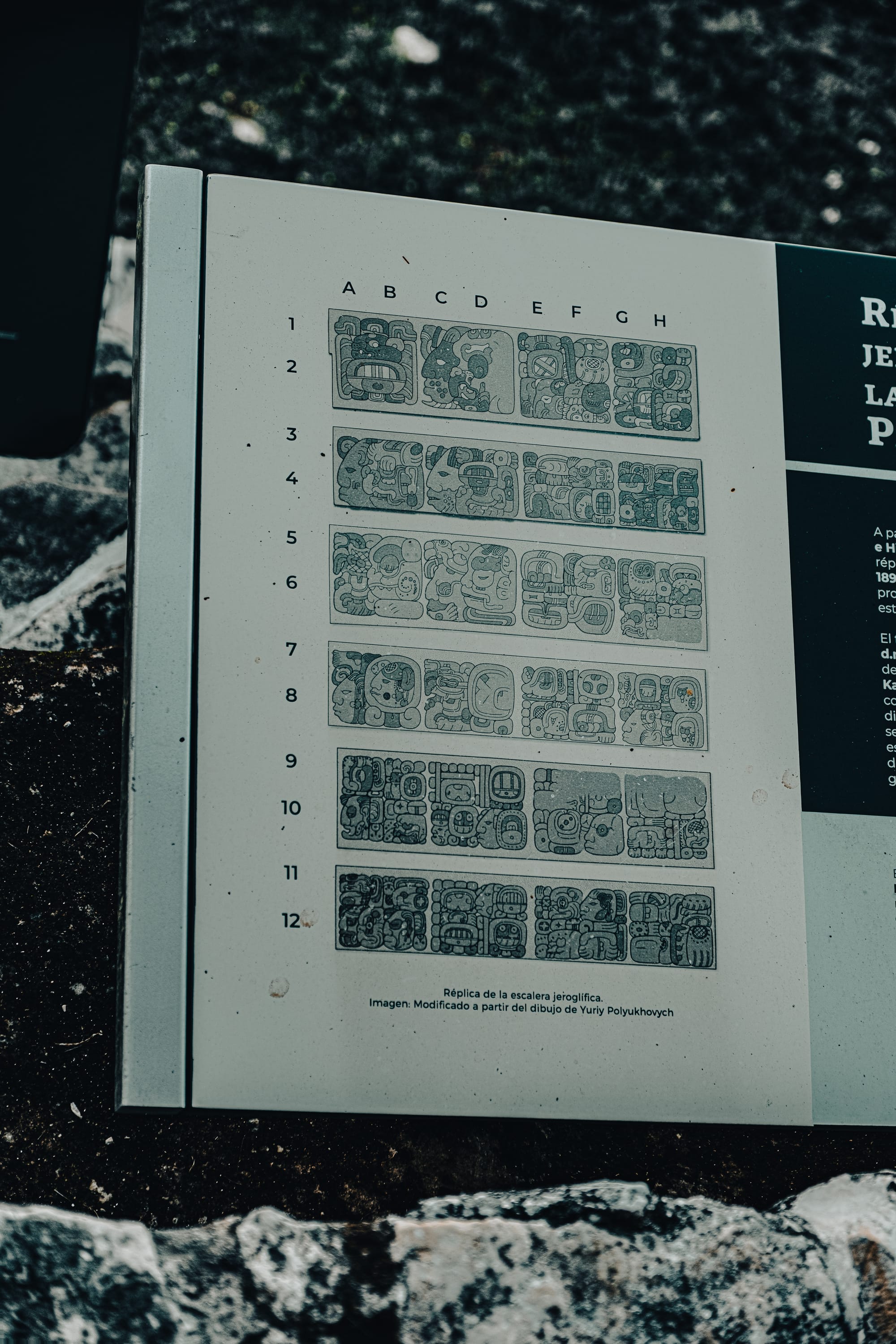

Under Pakal and his successors, Palenque developed some of the most refined stone carvings and inscriptions in the Maya world. These inscriptions have been crucial in helping archaeologists decode Maya writing and reconstruct dynastic histories.

Many of the most important inscriptions are concentrated around the Temple of the Inscriptions, but fragments and panels are scattered throughout the site. Some are crisp enough that individual glyphs stand out clearly: faces, knots, animal forms, calendar symbols. Others are softened by centuries of rain and humidity, their meanings partially eroded, their presence more textural than legible. You don’t need to read Maya script to feel the intention behind them—these were not decorative additions, but records meant to endure.

Carved glyphs, worn reliefs, and layered stonework reveal how Palenque’s history is written directly into its walls

What makes Palenque especially significant in the study of Maya hieroglyphic writing is the narrative depth of its texts. Many inscriptions here document dynastic events with unusual clarity: royal births, accessions to power, military victories, deaths, and ritual observances tied to the Maya calendar. Through these carvings, Palenque became one of the key sites that allowed scholars to move beyond seeing Maya glyphs as purely symbolic and begin reading them as historical language.

Daily life in Palenque: what the archaeology reveals

At its height in the 7th and early 8th centuries CE, Palenque was continuously inhabited by thousands of people, with daily life unfolding across residences, cultivated land, and shared civic space.

Food production shaped much of everyday experience. Archaeological and environmental research shows that Palenque’s inhabitants relied on a combination of agriculture and forest management rather than large-scale monoculture. Maize formed the dietary base, supported by beans and squash, alongside chili peppers, cacao, and various root crops. Evidence from pollen and soil analysis suggests food was grown close to where people lived, using terracing and managed landscapes. This meant daily routines were closely tied to nearby fields, water sources, and household food preparation rather than distant agricultural zones.

Craft production was similarly woven into daily life. Palenque is especially known for its stone carving, and evidence indicates that sculptors and scribes were highly trained specialists working in close connection with the ruling court. Inscriptions and reliefs were not static artworks but part of an ongoing process—planned, carved, revised, and maintained over time.

Stone walls, jungle edges, and elevated walkways weave together

Beyond elite production, non-elite households engaged in textile making, tool repair, and food processing, activities reflected in excavated tools and domestic remains.

Palenque had a clear social hierarchy. Inscriptions focus heavily on rulers and elites, whose lives revolved around ritual calendars, governance, and public ceremony. For most residents, daily life was materially focused but still deeply ritualized. Archaeological evidence from household contexts suggests that religious practice—ancestor veneration, offerings, and calendrical observances—was embedded in domestic space rather than confined to temples alone.

One constant across social levels was interaction with water and forest. Palenque’s engineered channels required continuous maintenance, making water management part of everyday labor and responsibility. The surrounding jungle was not a boundary but an active presence, supplying food, materials, and ecological stability.

Key structures to know before you visit

Temple of the Inscriptions

This is Palenque’s most famous structure and one of the most important archaeological discoveries in the Americas. The temple contains a long hieroglyphic text detailing the lineage of Palenque’s rulers.

In 1952, archaeologist Alberto Ruz Lhuillier discovered a hidden staircase inside the temple leading to Pakal the Great’s tomb—one of the richest and most intact Maya royal burials ever found. The stone sarcophagus lid depicts Pakal in a cosmological scene often misinterpreted in pop culture, but now understood as a symbolic representation of rebirth and the Maya underworld.

The Temple of the Inscriptions, monumental with its clean geometry

Visitors cannot enter the tomb today, but standing before the structure gives important context to Palenque’s political and spiritual significance.

The Palace

The Palace is a sprawling complex of courtyards, corridors, and towers. It likely served administrative, residential, and ceremonial functions. The four-story tower is unusual in Maya architecture and may have been used for astronomical observation or ritual purposes.

From the upper areas, you get a sense of how integrated the city was with the surrounding jungle.

Temple of the Cross Group

This group includes the Temple of the Cross, Temple of the Foliated Cross, and Temple of the Sun. Together, they form a ceremonial complex dedicated to Palenque’s ruling dynasty and Maya cosmology.

Temple of the Cross

The carvings here are among the most detailed in the Maya world, depicting rulers in ritual contexts alongside cosmological symbols connected to creation myths.

Exploring without a guide

You can hire a guide at the entrance to Palenque, and many visitors choose to do so. Guides can provide valuable historical context, especially if you’re unfamiliar with Maya history.

We chose to explore independently.

This allowed us to move at our own pace, spend more time in areas that interested us, and linger where the site felt particularly resonant. Informational signage throughout the ruins is generally clear and well-maintained, making self-guided exploration very feasible.

Light protection and narrow passageways frame fragments of relief and interior space

If you enjoy reading about a site beforehand and prefer a slower, self-directed experience, skipping a guide is a reasonable choice.

Experiential notes

Entering the Palenque archaeological site feels less like stepping into a single monument and more like drifting into a landscape that happens to be architectural. The jungle doesn’t recede at the edges—it presses in, folds around stone, throws shade across plazas, and hums constantly in the background. Even early in the day, the air is warm and dense, softened by canopy cover and the sound of water moving somewhere just out of sight.

Water channels and canopy overhead quietly shape the rhythm of the site

The first thing we noticed was scale—not in the sense of enormity, but in how spread out Palenque is compared to other Mayan ruins in Mexico. Wide grassy courtyards open suddenly between structures. Stone pathways curve gently rather than forcing you in straight lines. You’re walking, then pausing, then walking again—often without realizing how much ground you’ve covered.

Souvenirs, reproductions, and everyday commerce sit at the edge of the ruins

The Temple of the Inscriptions rises slowly into view rather than announcing itself all at once. Its stepped pyramid form is clean and geometric, but softened by time and vegetation.

Standing in the main plaza, it’s impossible not to feel the deliberate placement of this structure within the broader landscape. Visitors move more quietly here. People stop longer. Cameras lower.

From there, wandering toward the Palace, the experience shifts. This complex feels lived-in in a way that’s different from the ceremonial clarity of the temples. Long corridors cast deep shade. Stone walls are close enough to brush with your hand as you pass.

The Palace unfolds as a series of rooms and courtyards

From certain angles, the Palace tower rises above the trees, offering one of the clearest reminders that Palenque was once not just a spiritual site, but a functioning city—administrative, residential, and political.

One of the most striking things about exploring Palenque independently is how often your attention is pulled downward rather than upward. Stone carvings, worn stair edges, fragments of reliefs embedded in walls—details reveal themselves slowly. Some glyphs are sharp and legible; others are eroded to near abstraction.

Stone carvings at Palenque

Walking farther into the site, the jungle becomes more present. Trees arch over secondary temples. Light breaks unevenly through leaves, creating sharp contrasts between sunlit limestone and deep shadow. At times, it feels as though the ruins are emerging from the forest rather than the other way around. This is one of the defining characteristics of the Palenque Mayan ruins—they are not isolated from their environment, but actively entangled with it.

Palenque's dense jungle

We spent time sitting on low stone walls, watching other visitors cross the open lawns, listening to guides speak in Spanish, English, and French. Even at moderate crowd levels, Palenque absorbs people well. There’s space to step away, to linger alone, to circle back to a structure that caught your attention earlier.

Stone steps disappear into the forest

By the time we completed a loose loop through the main sections of the site, more than two hours had passed without effort. That’s the quiet power of Palenque.

Jungle growth quietly reclaims edges

Leaving the site, the jungle soundscape continues almost uninterrupted.

Extending the trip: Yaxchilán and Bonampak

If you have additional time, Palenque serves as a base for visiting two of the most remarkable—and remote—Maya sites in southern Mexico: Yaxchilán and Bonampak.

Yaxchilán is accessed by boat along the Usumacinta River and is famous for its intricately carved lintels. Bonampak is best known for its vivid murals, which depict courtly life, warfare, and ritual in extraordinary detail.

These sites require a long day and significant travel logistics, but they offer a deeper glimpse into Maya civilization for those willing to make the effort. We didn't get a chance to see these sites this time, but we hope to return to Chiapas again, and these are at the top of our list.

For travelers who prefer an organized option, this Yaxchilán, and Bonampak day tour from Palenque is one of the most straightforward ways to visit if you already have your visit to Palenque arranged. Alternatively, this 3-day tour from San Cristóbal organizes a visit to all three sites: Palenque, Yaxchilán, and Bonampak.

Book your visit

Palenque stands out not just because of its history, but because of how that history exists within the jungle. The ruins are not cleared away from nature; they are actively entangled with it.

Paired with nearby waterfalls like Misol-Há, this weekend trip offers a concentrated experience of Chiapas’ archaeological, ecological, and geographic diversity.

If you’re choosing just one excursion from San Cristóbal de las Casas, Palenque is the one we would return to.

For those who don't have time for a full weekend trip, we'd recommend this day tour from San Cristóbal to Palenque with Misol-Ha. However, if you have a few spare days, this 3-day tour from San Cristóbal to Palenque including Yaxchilán and Bonampak would be a great option.

Further information on Palenque

Is Palenque worth visiting from San Cristóbal?

Yes, absolutely. It’s a long journey, but the site is one of the most significant Maya ruins in Mexico. It was our favorite trip from San Cris.

Can you do Palenque in one day?

Yes, but it’s tiring. An overnight stay is strongly recommended. We've met people who did it in a single day and regretted that they didn't spend a night there.

How long should I spend at the ruins?

At least two hours, but three to four is ideal.

Is a guide necessary?

No. The site is well-marked, and self-guided visits are common. If you prefer a guided tour, you can easily find a guide near the entrance.

When is the best time to visit Palenque?

Early morning for cooler temperatures and fewer crowds.