El Cerrillo wakes early. Before the tourists reach Real de Guadalupe or the sound of marimbas rises from the plaza, the barrio hums under a low mountain light: dogs stretching, tamale steam clouding narrow cobblestones, and paint flaking from doorframes the color of dusted clay. Here, the walls are memory, manifesto, and map.

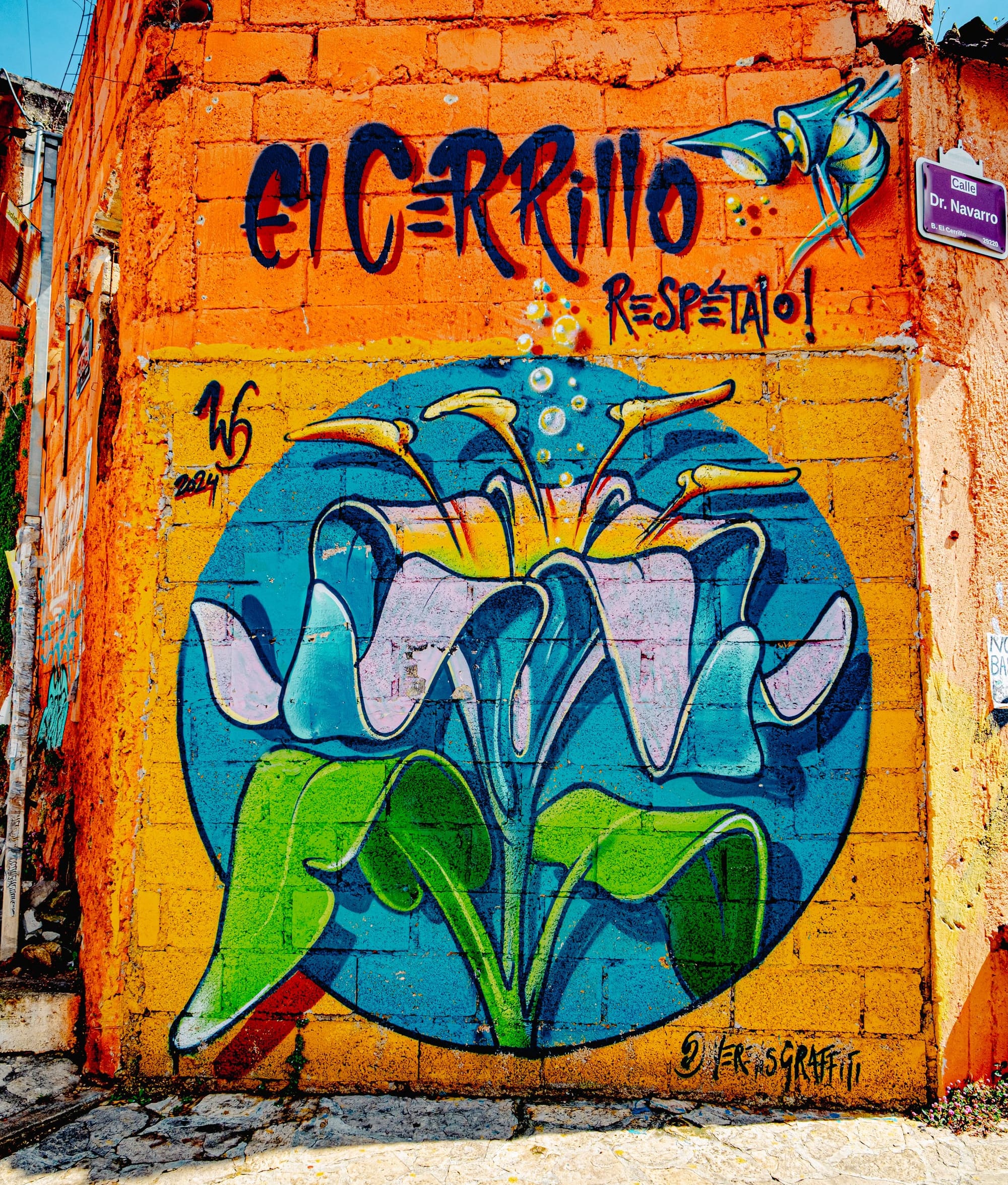

Colorful El Cerrillo murals celebrate resistance, EZLN heritage, and neighborhood pride

San Cristóbal de las Casas holds dozens of barrios históricos, each with its own pulse, but El Cerrillo carries a particular electricity. One of the city’s oldest quarters, it grew along the edge of the colonial grid, a settlement of Indigenous Tzotzil and Tzeltal families who came down from the highlands to trade wool, amber, and weaving.

Historic San Cristóbal streets and mural art meet in El Cerrillo

The barrio takes its name from a small hill crowned by the chapel of El Cerrillo San Cristóbal, built in the late 17th century, from which the city’s first fireworks once signaled local festivals. Over centuries, the hill became a threshold between center and periphery, colonial and communal—an in-between geography that has long attracted makers, migrants, and muralists. It is, in every sense, an "alternative neighborhood."

A wall becomes a workshop

Walking along Calle Real de Guadalupe toward the north, the tourist gloss begins to fade. Coffee roasters and co-ops appear in converted homes. On Calle Belisario Domínguez, the walls shift: bright acrylics on sun-burnt adobe, stencil portraits layered with moss. Here a masked Zapatista figure, eyes level with passing children. There a painted woman emerging from maize, hair interwoven with the constellation of Chiapas pueblos.

Many of these murals trace back to community collectives that have worked quietly since the 2000s. Their projects began after the 1994 Zapatista uprising, when young artists from rural Chiapas and San Cristóbal’s universities sought new ways to translate the movement’s autonomy into image.

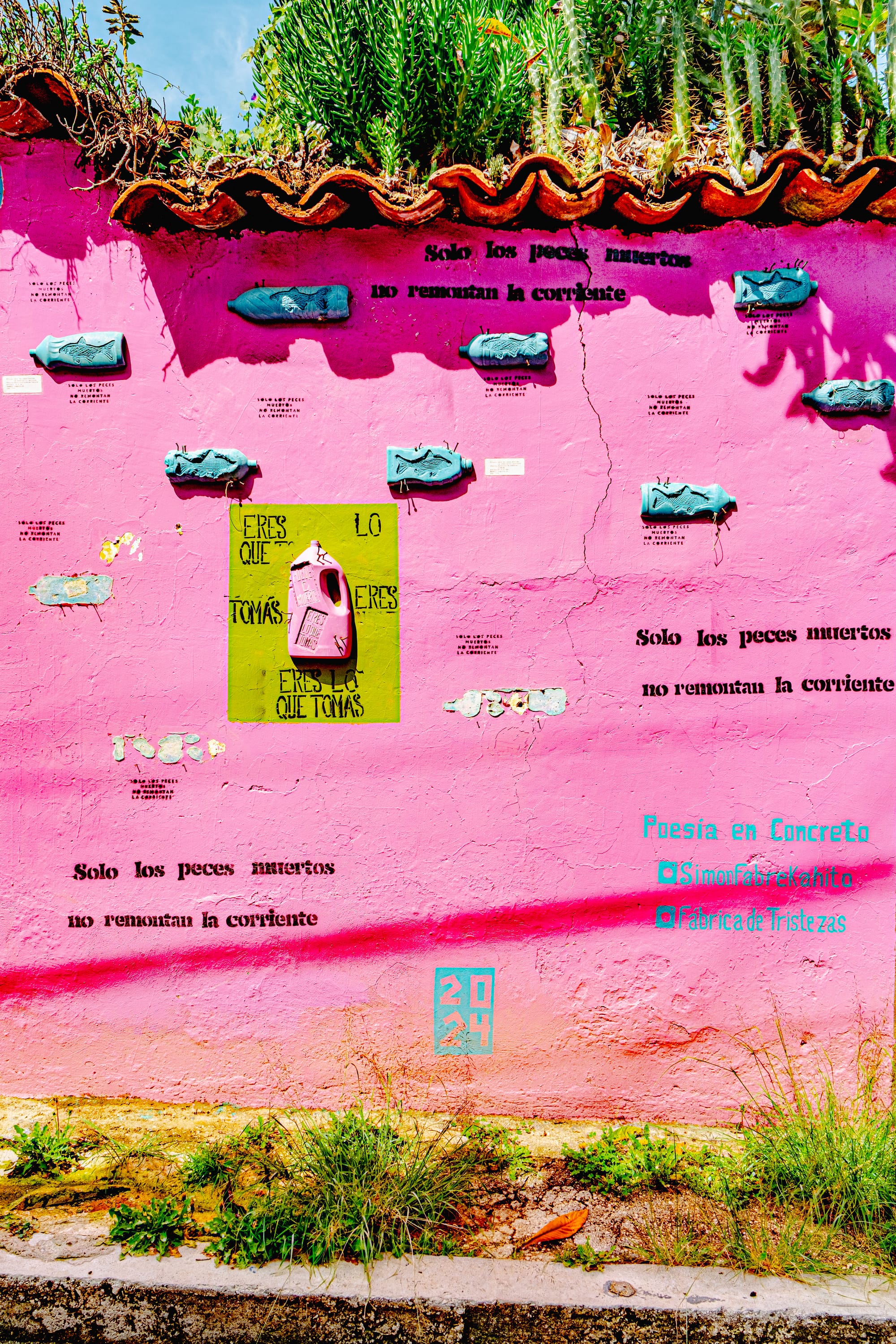

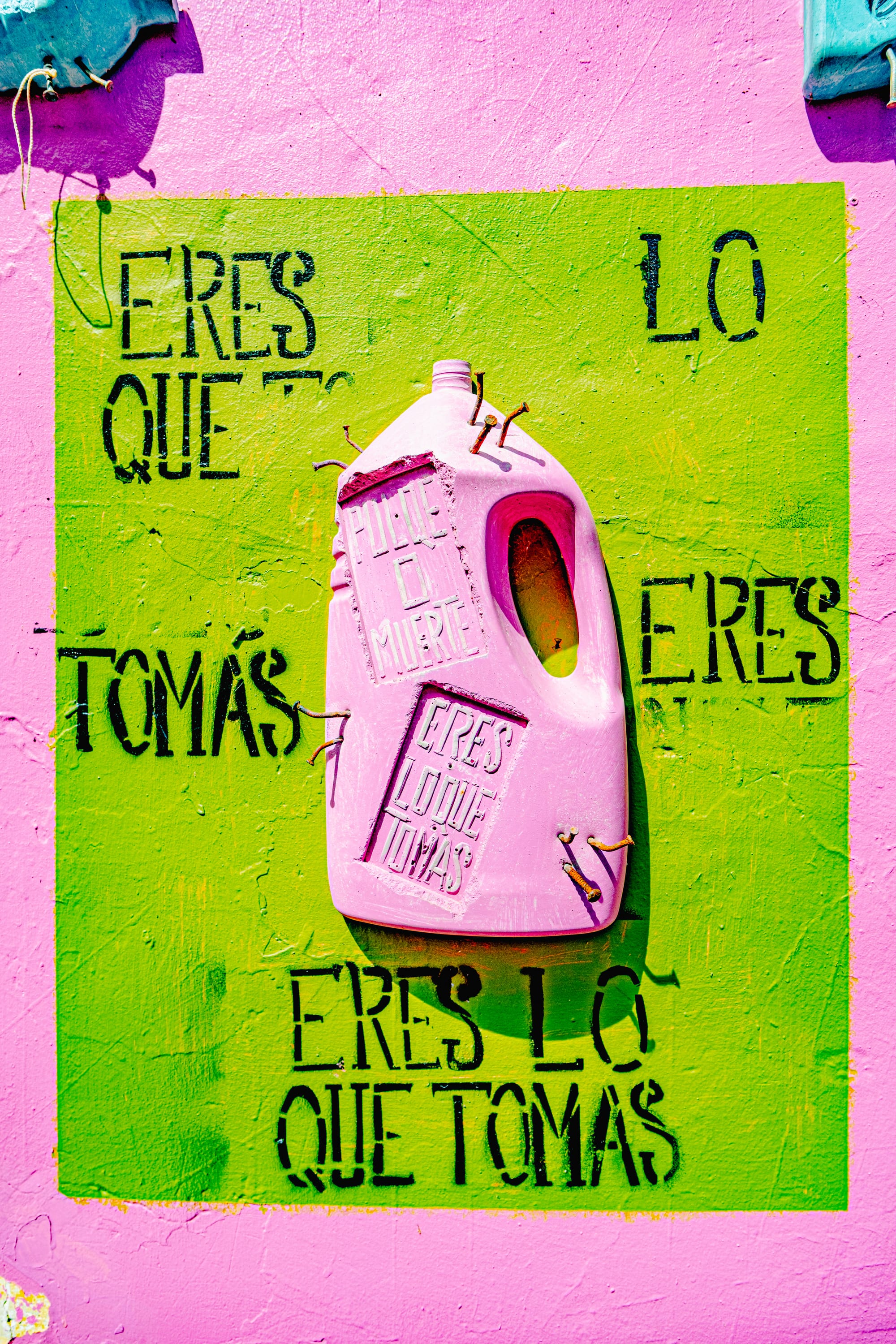

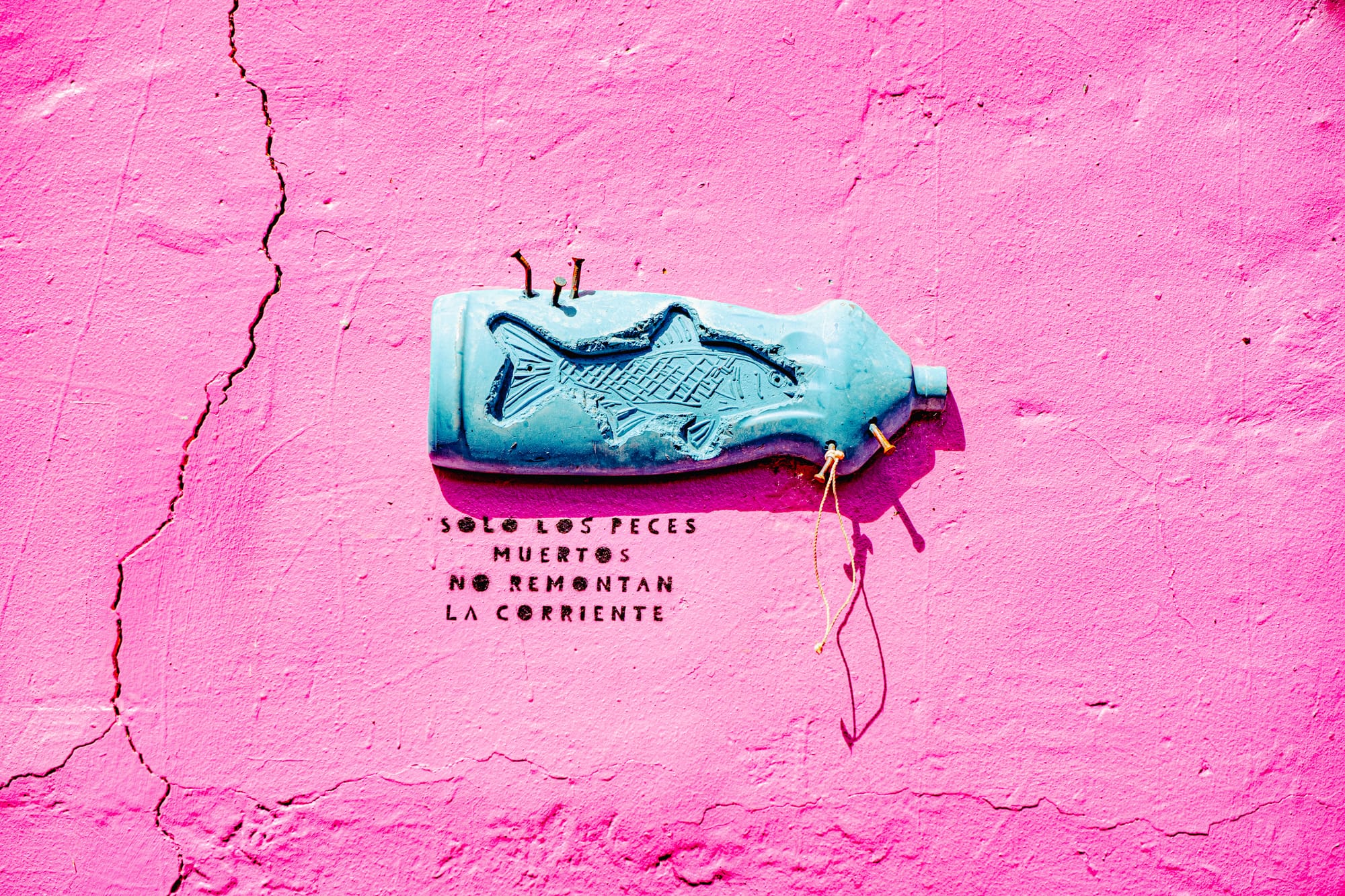

Recycled plastic sculptures in El Cerrillo critique consumption and water pollution

The technique is distinctly southern. No glossy aerosol gradients; brushes and house paint dominate, occasionally mixed with earth pigments or soot. The surface texture—the humidity cracking pigments into scales—is part of the aesthetic.

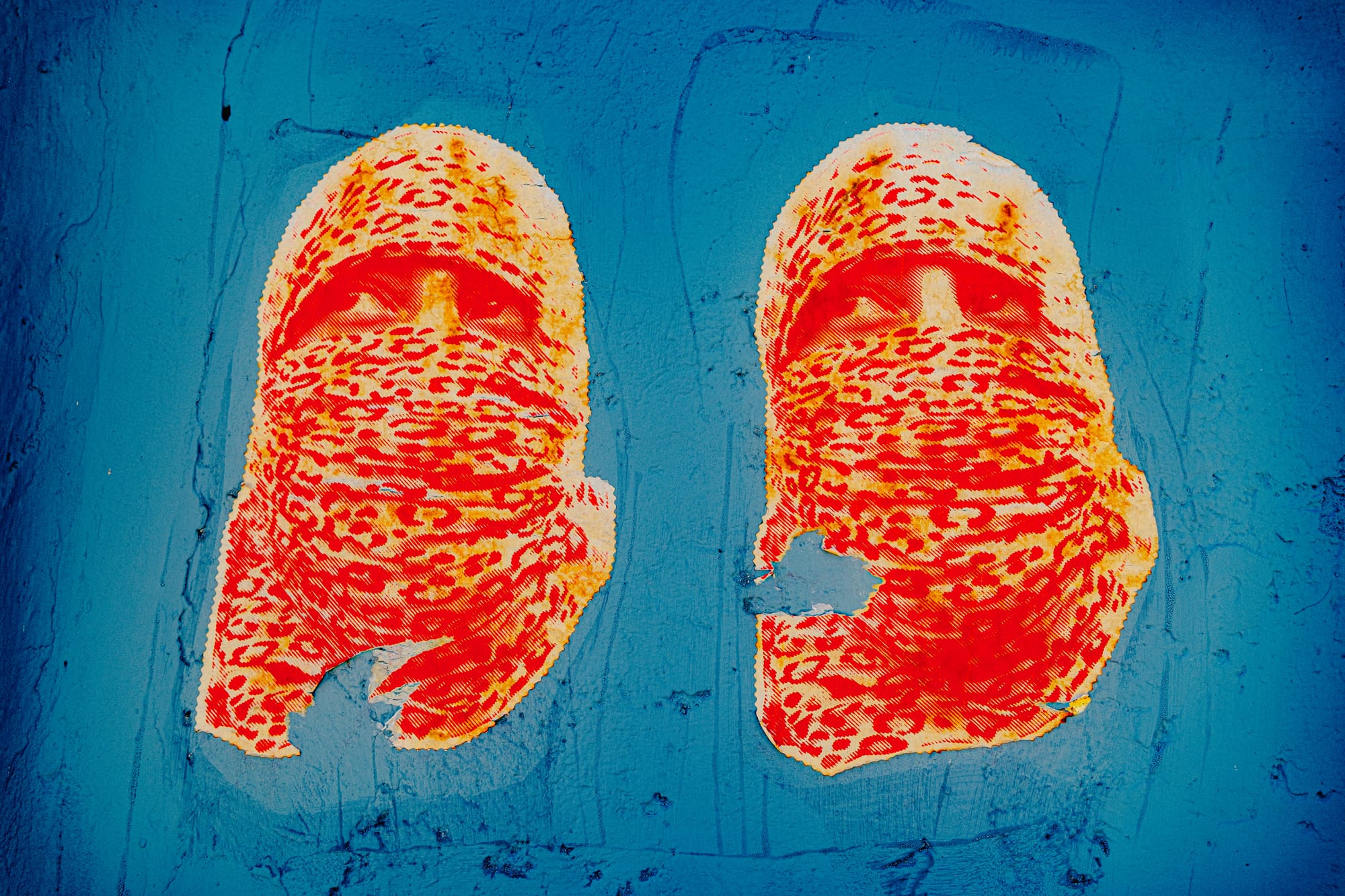

Street art in El Cerillo

Many images weave Mayan cosmology with anti-colonial critique: snakes sprouting corn, masked women carrying books and seeds, and jaguars.

Others are devotional: tiny murals to the Virgin of Guadalupe beside feminist slogans, hearts wrapped in barbed vines that echo both Catholic and Indigenous symbology.

Layers of resistance

El Cerrillo’s walls are layered like the city’s politics. Beneath each coat of paint lies another era of tension: colonial suppression, liberal reforms, paramilitary incursions, and gentrification. When students paint alongside neighborhood kids, they inherit that sediment.

Since the mid-2010s, new waves of artists, many women and queer collectives from San Cristóbal’s independent scene, have widened the vocabulary.

Across the barrio, the imagery converses with the political graffiti left during student marches or Zapatista anniversaries. The coexistence is intentional. Unlike the heavily touristic murals of Guadalupe Street or the curated “art walks” organized downtown, El Cerrillo’s walls are not beautified. A mural may share space with laundry lines, election posters, or the daily dust kicked up by colectivo vans. The art here is inseparable from habitation.

The barrio

Historically, El Cerrillo functioned as the northern hinge between the colonial grid and the Indigenous barrios beyond—Cuxtitali, Mexicanos, and La Merced. In the 1960s and 70s, as migration from surrounding highlands increased, its steep alleys became home to artisan families producing textiles and amber jewelry. Workshops opened in patios, combining Indigenous craft traditions with urban access. Many of today’s muralists are descendants of those artisans, their visual language extending the loom onto stucco.

Contrasting murals in El Cerrillo explore time, memory, and spiritual renewal

But the neighborhood’s location has also made it a frontier of gentrification. The same cobblestones that carry revolutionary slogans now host boutique hostels, yoga studios, and coworking cafés run by remote workers. A two-room house that once sheltered four generations may rent for the monthly salary of a local teacher. In this context, street art becomes a mode of territorial claim, a refusal painted in ochre and green.

Iconography of autonomy

Certain motifs recur like protective spirits. The corn plant, always central, often appears emerging from women’s bodies—recalling the Mayan creation myth of humanity born from maize. Masks—half Zapatista, half jaguar—symbolize both anonymity and continuity.

The city’s official circuits often omit El Cerrillo, favoring gallery-friendly aesthetics. Yet through alternative mapping, the barrio re-inscribes itself into visibility.

Street art stickers in El Cerrillo mix Zapatista imagery with cosmic symbolism

It would be easy to romanticize this landscape of color and rebellion, but the truth is more ambivalent. Some residents see the murals as symbols of pride; others view them as reminders of neglect, paint filling gaps left by absent services. Still, most agree the art has kept a sense of community alive.

The eyes that watch back

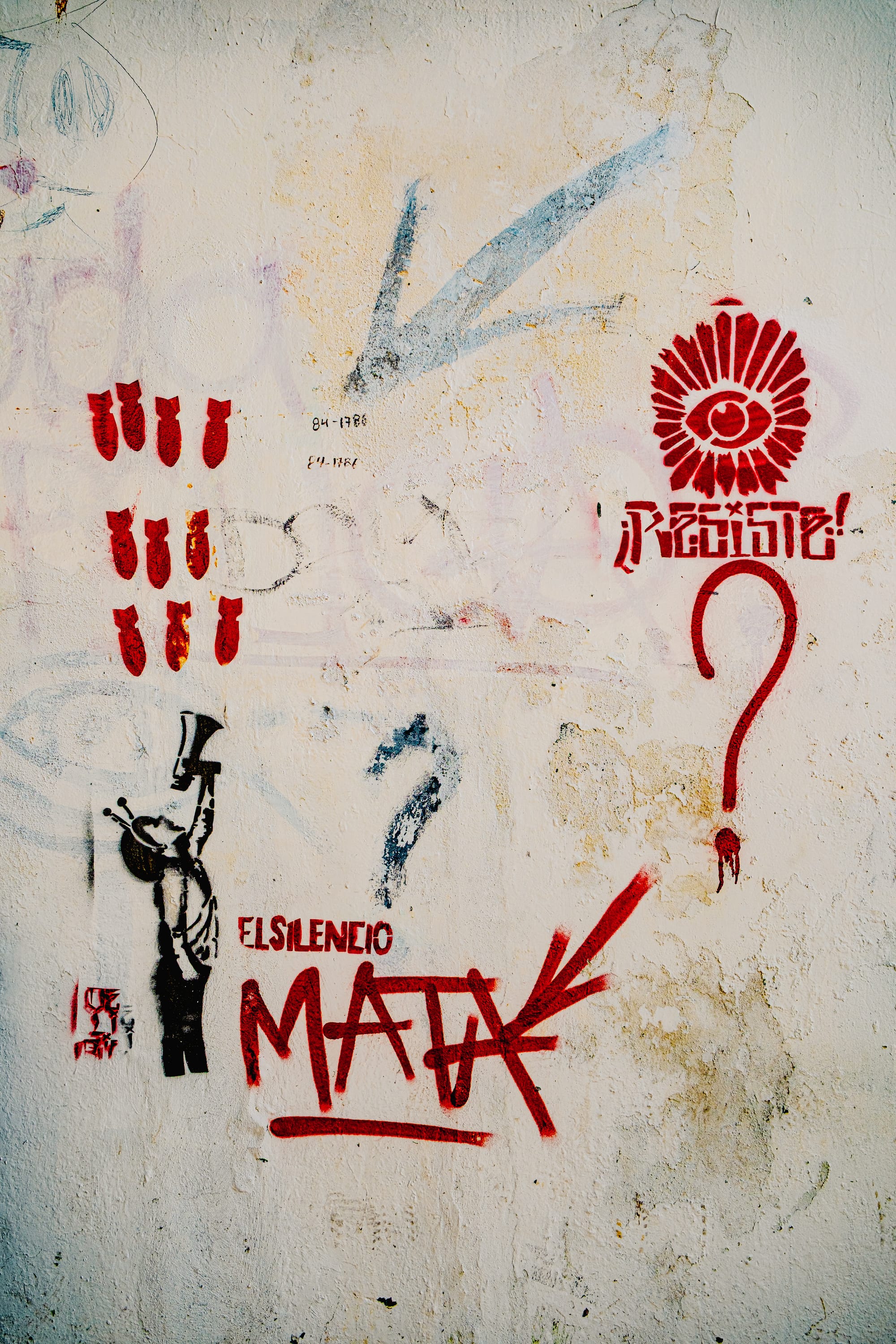

Walk long enough through El Cerrillo and you’ll start to notice them: eyes painted on corners, electrical boxes, the backs of street signs. Sometimes singular, sometimes in clusters, always watchful. Beneath many of them, a spray can appears mid-action, painting over a surveillance camera. Around the image, one of two words: resiste or deliria. The motif has spread beyond the barrio now, but El Cerrillo remains its origin.

The eye has no single author, to our knowledge. We imagine it began as a collective intervention—a recurring, anonymous response to the growing presence of surveillance. Artists use it as a visual reclamation of gaze: the watcher watched. Each repetition slightly altered—the iris a different color, the spray angled differently, the word shifting tone. It’s a neighborhood signature by now, a symbol of how El Cerrillo protects its own visibility.

Playful and surreal street art in El Cerrillo blends humor with quiet defiance

In a city where surveillance increases as public art funding wanes, the motif flips the power dynamic.

The taste of resistance

Another recurring subject on El Cerrillo’s walls is less abstract: the red wave of Coca-Cola. In Chiapas, Coca-Cola is more than a beverage—it is a system. The multinational operates a massive bottling plant on the outskirts of San Cristóbal, drawing water from the same aquifer that supplies local communities. During dry seasons, taps run dry in Indigenous neighborhoods while the company’s trucks keep rolling, full and cold. Protest murals throughout the city, especially in El Cerrillo, have made this visible.

Mural in El Cerrillo contrasts flowing maize imagery with Coca-Cola’s corporate logo

For years, activists and residents have demanded restrictions on corporate water extraction, linking it to shortages and health crises. Through this conversation of symbols, El Cerrillo’s walls turn corporate critique into communal catechism.

Street murals in El Cerrillo denounce Coca-Cola’s water extraction with biting humor

Coca-Cola’s dominance also manifests culturally. In the highlands, the drink has replaced traditional beverages in ceremonies, its logo often coexisting with crosses and candles in village rituals. Some murals address this directly: bottles inverted into crucifixes, fizz turning to smoke. These images blur satire and lamentation. In them, capitalism and colonialism are not abstract forces—they’re daily ghosts haunting the market shelves.

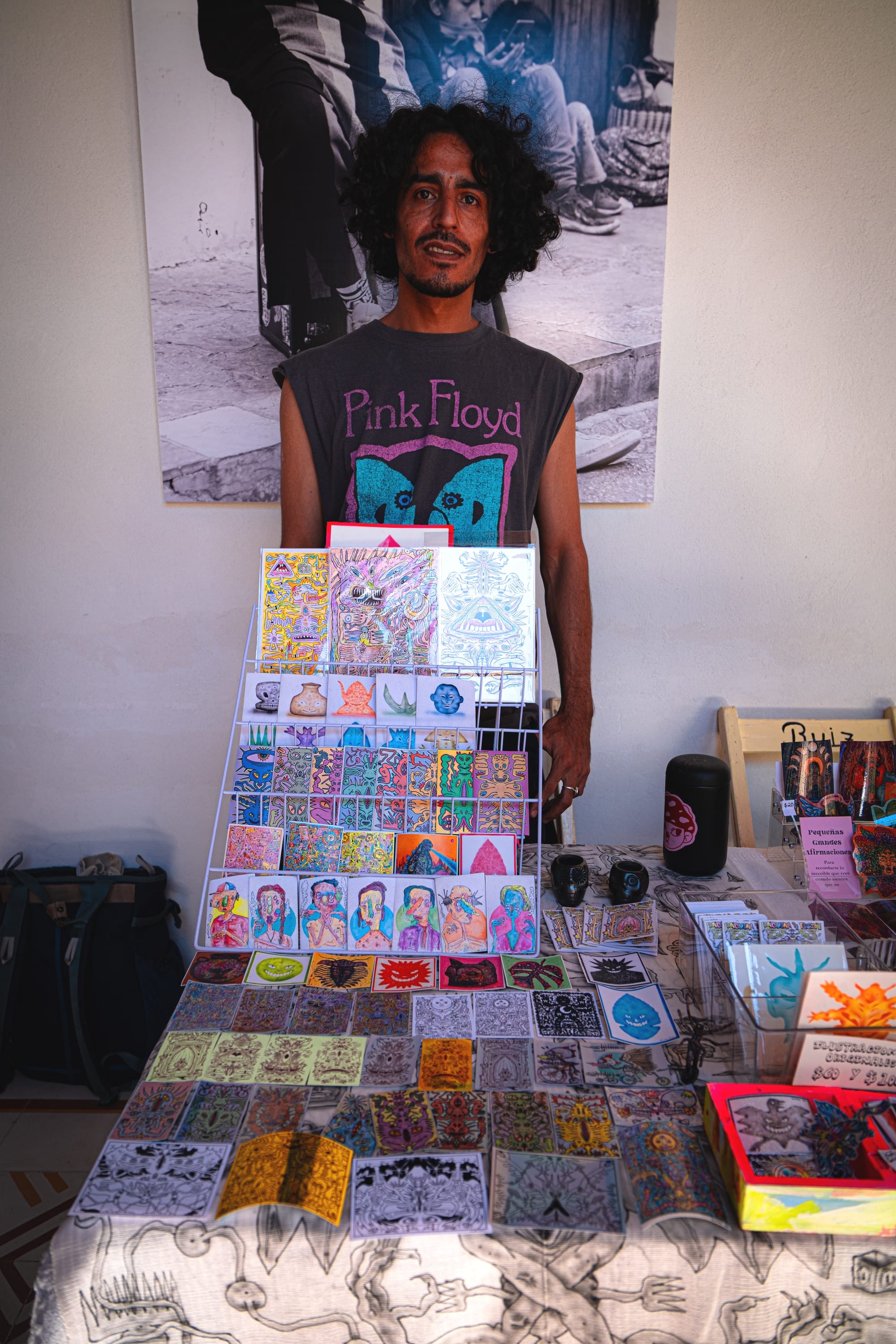

Meeting Carlos Cea

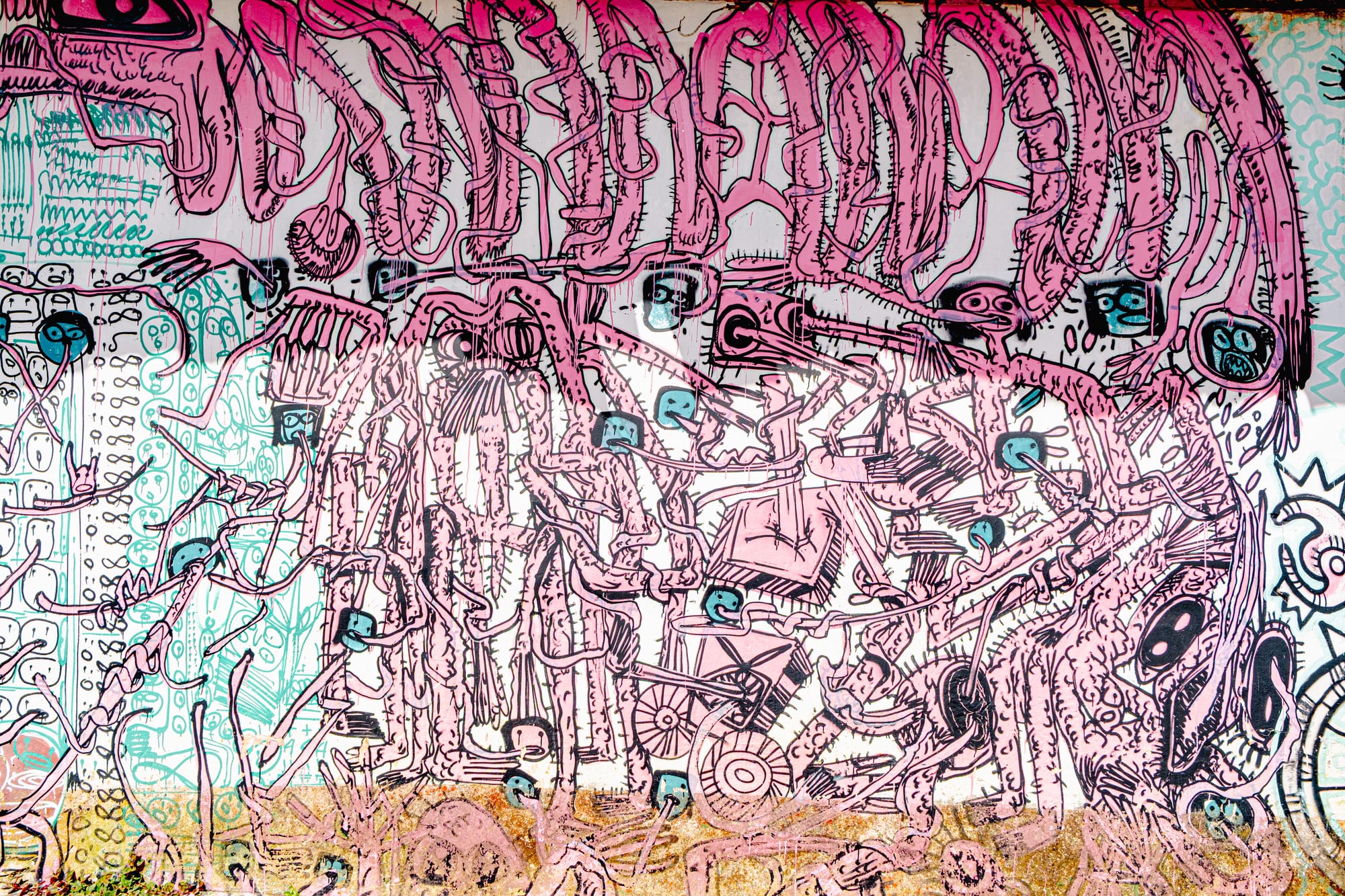

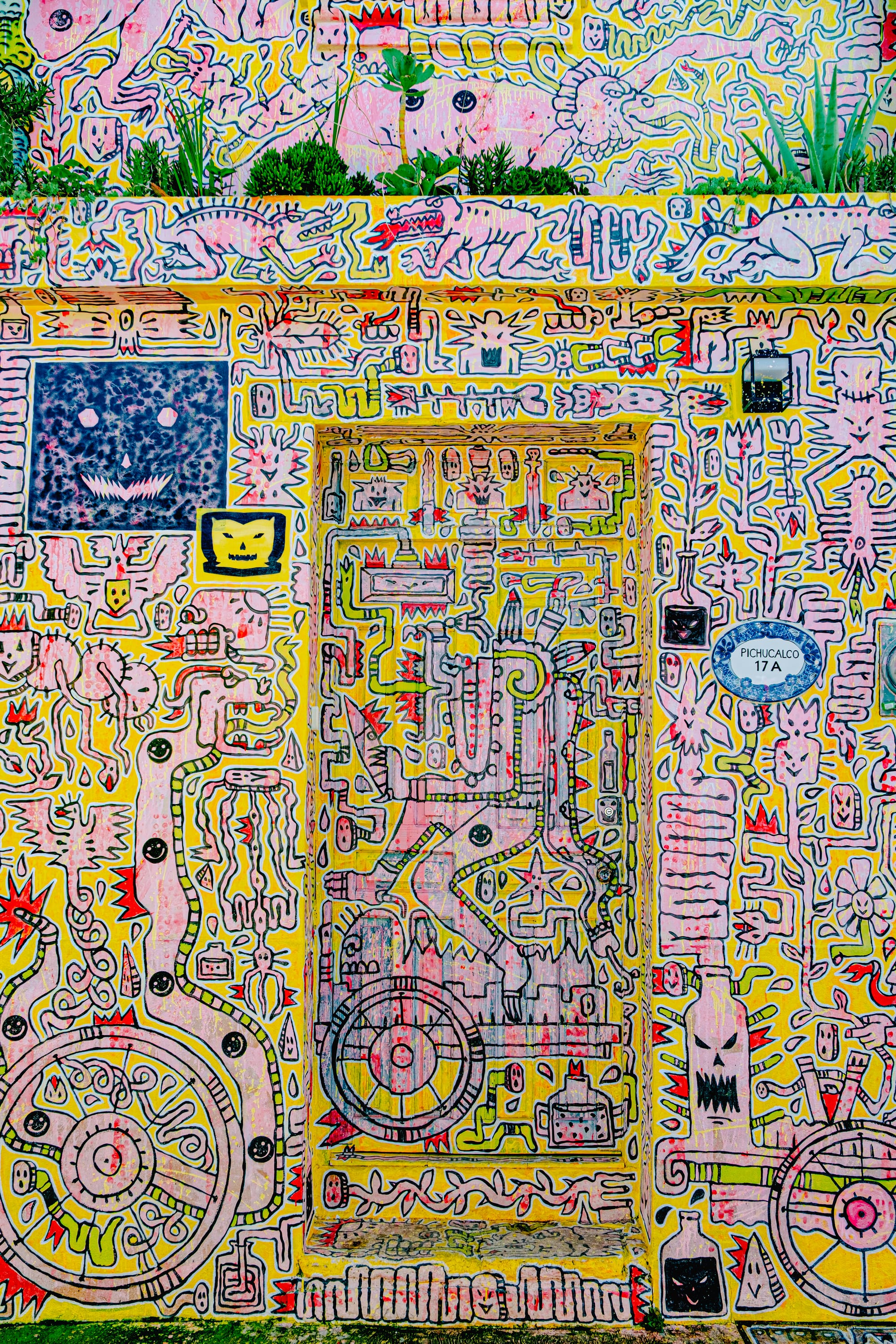

The sticker fest we visited one afternoon brought the movement into human scale. Artists traded prints, zines, and fragments of walls on paper. Among them was Carlos Cea, one of El Cerrillo’s most prolific muralists, known for his organic abstractions that merge animal, human, and plant forms in layered fields of color. His style is unmistakable: broad brushstrokes that blend psychedelia with local symbolism.

Cea’s murals climb alleyways and spill into courtyards, each one rooted in the soil of Chiapas yet infused with dream logic. He paints with reverence for the everyday: the basket seller, the mountain, the stray dog, the rhythm of rain. Seeing him at the festival, surrounded by his stickers and small prints, felt like meeting the hand behind the neighborhood’s quieter magic.

Carlos Cea and his intricate murals connect everyday life with cosmic imagination

His practice mirrors the barrio’s ethos—slow, relational, and community-anchored.

Gendered walls, collective hands

The mural movement in El Cerrillo has long been sustained by women and queer artists who find in public space a form of reclamation. Imagery often centers bodies in motion—women planting maize, holding children, carrying protest banners—but rendered with tenderness rather than heroism.

Murals in El Cerrillo honor Indigenous women’s strength, labor, and collective resistance

During recent years, as femicide rates in Chiapas rose, these collectives transformed their painting sessions into acts of mutual protection.

These works converse with the more politically explicit pieces nearby. The multiplicity—some devotional, some angry, some surreal—reflects El Cerrillo’s deeper truth: that art here is not singular or programmatic. It’s ecological, entangled. Each mural is both symptom and seed.

Art as social glue

In El Cerrillo, murals function as social glue in a precarious economy. When formal work is scarce and rent climbs, collective art-making becomes both labor and livelihood.

Artists trade skills for meals, apprenticeships for shelter, murals for shared recognition. The walls record these exchanges not as signatures, but as continuities—proof that interdependence can still be a viable economy.

Between tourism and territory

Today, the paradox of El Cerrillo intensifies. As murals attract attention, new cafés and rental properties follow. Travelers arrive seeking authenticity, unaware that each photo adds to the cycle of commodification.

El Cerrillo’s murals and stickers celebrate color, memory, and neighborhood identity

Yet within this tension lies resilience. Artists like Cea and the collectives continue to paint, teach, and organize, transforming potential exploitation into opportunity for dialogue.

Closing the circle

At night, the murals soften. The eyes on the walls glimmer in the half-light of passing motorcycles. Rain glosses the cobblestones, carrying the scent of acrylic down the hill. Somewhere, a band practices cumbia; a child traces a heart into drying paint. The barrio breathes.

El Cerrillo’s street art how neighbors recognize one another across time, and how histories of colonization, extraction, and care remain visible.