When people picture São Miguel in the Azores, they often think of crater lakes, thermal springs, or volcanic cliffs wrapped in mist. But on the outskirts of Ponta Delgada, there’s a quieter kind of magic growing under glass: pineapples. And not just any pineapples—some of the only greenhouse-grown pineapples in the world, cultivated through a slow, meticulous process unique to the Azores.

At Plantação de Ananás dos Açores, you’re invited into that process. No ticket booths here—just rows of steamy greenhouses, a path under your feet, and a long lineage of island agriculture unfolding leaf by leaf.

This small plantation is one of the best places to experience the quiet art of Azorean pineapple farming up close. It’s not a long visit, but it leaves a lasting impression.

A tropical fruit in Atlantic soil

Pineapples aren’t native to the Azores. They were introduced in the 19th century—brought from Brazil by Portuguese colonists—after the decline of São Miguel’s orange exports. The fruit thrived, but only under protection. Unlike in tropical regions, pineapples couldn’t grow in the island’s mild maritime climate without help. The solution? Glass.

What began as an agricultural experiment eventually became an enduring part of São Miguel’s cultural and culinary identity.

Over the next century, a network of pineapple greenhouses was developed—simple but effective structures that trapped sunlight, retained warmth, and allowed for a slow, careful cultivation process that continues today.

But unlike commercial pineapple farming in tropical zones, which can produce fruit in 9–12 months, the Azorean process takes almost two full years. There are no chemical shortcuts here—just natural fermentation beds, organic mulches, and an intricate choreography of warmth, moisture, and time.

The result is a smaller fruit—more acidic, more fragrant, more alive with flavor. If you only ever eat canned or mass-market pineapple, the Azorean version will taste like a rediscovery.

It’s one of those rare things that lives up to its own quiet reputation.

A walk through the greenhouses

As you step inside the first greenhouse, you’re met with rows of spiky plants emerging from a blanket of dark volcanic soil and cotton-like matting. There’s an earthy sweetness in the air—warm and slightly damp, with just a hint of smoke from the traditional heating techniques.

Some plants are just beginning to bud, their tips topped with tight spirals of pale green.

Others are well along: dark, glossy pineapples nestled in the cradle of their stiff, arching leaves.

Two pineapples at different stages of ripening, growing slowly under glass

Every row has its own energy. Some greenhouses feel still and steamy, others open and sharp with the smell of sun-warmed leaves.

Early-stage pineapples forming low to the ground, nestled in rows of spiked leaves and volcanic matting

These greenhouses are tactile spaces. The mesh underfoot is fraying. Rust runs down the iron poles. But that’s part of the charm—this is agriculture in motion, not a showroom.

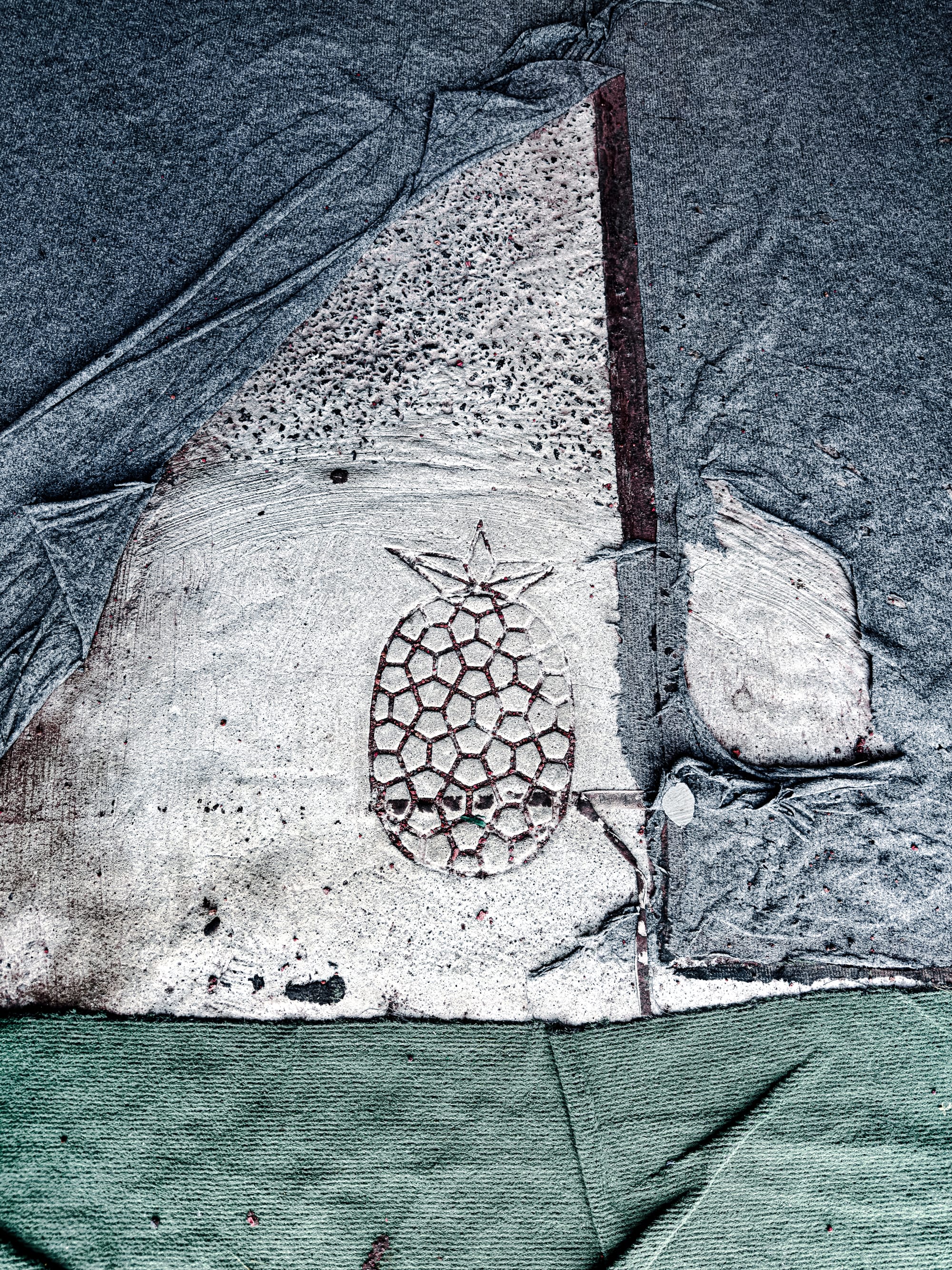

As you walk the narrow paths between rows, you might look down and notice concrete tiles etched with pineapple emblems—a kind of agricultural sigil. It’s a small, repeated gesture that reinforces how deeply this fruit is woven into the island’s identity.

Pineapple etchings—a small but lasting tribute to the island’s agricultural identity

Details like these give the space its texture—part botanical, part archival.

A living tradition

This isn’t just farming—it’s continuity. Many of the techniques used today were passed down over generations. Soil is still enriched with organic composts like fig leaves and seaweed. The greenhouses are warmed naturally, and the fruits are harvested by hand.

While some plantations have shifted to tourist-only models, Plantação de Ananás dos Açores still grows pineapples for consumption, export, and research.

And it’s not just a historical curiosity. Azorean pineapples are protected under the EU’s PGI (Protected Geographical Indication), like Champagne or Parmigiano-Reggiano. That means the pineapples grown here can’t be replicated elsewhere—and you can taste why.

Outside, a colorful triptych mural tells a visual story of the plantation: workers harvesting pineapples, women holding fruit, birds in motion. The style is simple and expressive, almost folkloric. It reminds you that agriculture here isn’t just about produce—it’s about people, labor, history.

It’s worth pausing here. The mural says what words sometimes can’t: this work is care.

The pineapple juice alone is worth the stop

After wandering through the greenhouses, the on-site café offers a final sensory reward: cold pineapple juice, served in a glass shaped like the fruit itself.

The juice is golden, slightly frothy at the top, with a hit of tartness that tastes like sunlight. It’s the kind of drink that surprises you in its simplicity—sweet, yes, but also sharp and clean, with none of the syrupy flatness of store-bought versions.

You can also buy fresh fruit, pineapple liqueur, or housemade jams—perfect gifts, especially if you want to share something that actually tastes like the Azores.

Plan your visit

You can visit Plantação de Ananás dos Açores independently (for free), or as part of a tour, such as this full-day island tour, which includes a stop there.

Whether you come for ten minutes or an hour, the place has a way of staying with you. It’s simple, slow, and deeply São Miguel.