Tucked in the heart of Demre, the Church of Saint Nicholas is a quietly arresting site—not simply for its religious significance, but for the astonishing detail it holds within its walls, its ceilings, and even its fractured courtyards. Unlike many ancient ruins in the Lycian region, this one retains an unexpected vibrancy: traces of color, elaborate stonework, and the layered presence of both faith and folklore.

We visited the church as part of a day-long tour that also included Kekova and Myra. With a rich Byzantine past and deep spiritual associations, it offered a beautiful atmosphere to explore every crevice.

A saint remembered, a space reimagined

Saint Nicholas—yes, that Saint Nicholas—served as bishop of Myra in the 4th century. Known for his compassion, defense of the poor, and deep Christian devotion, Nicholas became the basis for the modern Santa Claus mythology centuries later. But here in Demre, his memory is anchored in stone and icon, not snow and sleighs.

The church was built in the 6th century AD, over the site of the original burial place of Nicholas. Over the centuries, it has undergone multiple restorations, especially during the Byzantine and later the Russian Orthodox periods. A protective roof now shelters its fading murals and carved columns, while the interior layout reveals a basilica structure typical of early Christian architecture.

One of the most powerful elements of visiting this church is not just the history of the man it honors, but the sensory detail with which his story has been preserved.

Murals that speak in color

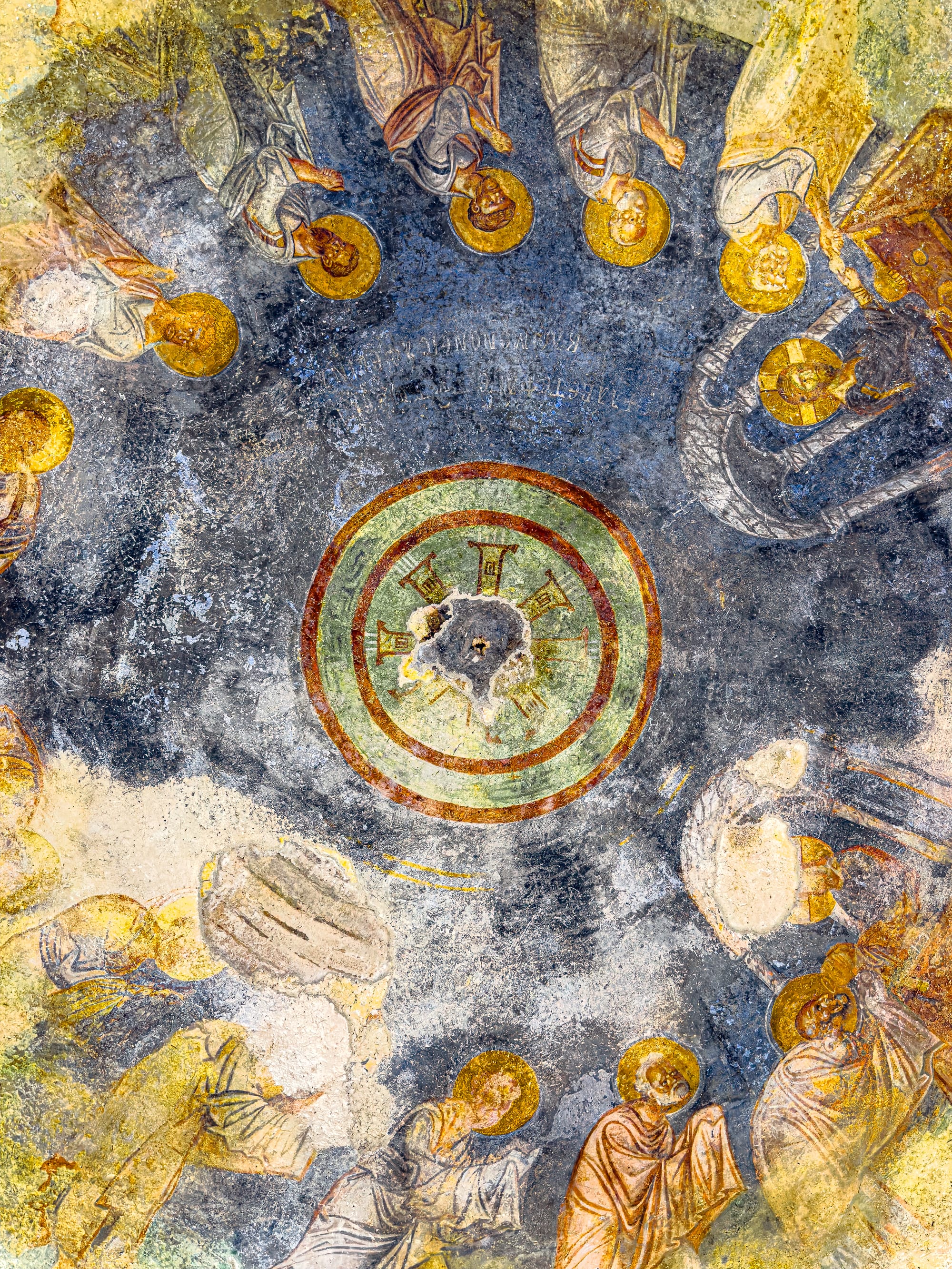

Perhaps the most unexpected feature of Saint Nicholas Church is the richness of its surviving murals. Faded but still legible, these frescoes wrap across arched ceilings, window borders, apses, and corridors. Though many are fragmented, the remnants still communicate stories with remarkable vibrancy.

Color and devotion linger across every surface

On one ceiling, you might spot Christ Pantocrator—Christ as ruler of the universe—seated in a medallion surrounded by seraphim. Nearby, saints and bishops are depicted in their full regalia, halos intact, their faces rendered in earth-toned ochres and reds. Angels flank altars. Processions wind their way along vaults. Scenes of martyrdom, resurrection, baptism, and ascension unfold in cinematic sequence.

What’s notable is not just the subject matter, but the color. Deep rusts, faded blues, smoky yellows—all still visible after more than a millennium. In the dim light of the church’s interior, the frescoes seem to glow from within, especially along the upper transept.

Halos gleam beneath centuries of wear, where saints still stand shoulder to shoulder in pigment and light

Many of the murals likely date from the 9th to 12th centuries, when the church was an important pilgrimage site.

Domed ceilings become illuminated vaults, where saints form radiant constellations around a sacred center

During this period, the visual storytelling would have offered a kind of didactic experience for visitors: teaching, inspiring, humbling.

Columns, capitals, and courtyard fragments

Stepping outside, the atmosphere shifts from hushed interior to sunlit archaeology. The open-air courtyard adjacent to the church is scattered with sculptural fragments—column capitals, decorative friezes, sarcophagus lids, and carved plaques.

Sunlit courtyards and shadowed thresholds mark the passage from civic stone to sacred interior

Some of the column tops are intricately scrolled, with Corinthian flourishes and geometric motifs. Others are simpler, weathered to abstraction.

Weathered symbols of protection and intricate vegetal carvings recall the church’s layered devotional history

Each piece feels like a sentence from a longer story, interrupted by time.

Fragments of early Christian stonework scattered like scripture, inscribed with geometry, florals, and cosmic symbols

These fragments are arranged not as static exhibits, but as a kind of broken syntax—visible, touchable, still echoing. You’ll also spot pediment stones that once crowned doorways or tombs. Their relief work includes vine motifs, rosettes, and Christian iconography.

A field of fallen columns and overgrown capitals, where sacred geometry meets slow decay

The courtyard is also home to modern statuary—including a sculpture of Saint Nicholas himself, hands outstretched, surrounded by mosaic insets.

Modern monuments, blooming oleander, and the bell tower silhouette frame the legacy of Saint Nicholas

Behind him rises the bell tower, and beyond that, the outer walls of the basilica, with their layered brick and stone construction.

Architectural choreography

The church’s floor plan follows a classic Byzantine basilica structure, with a central nave flanked by aisles and a semi-domed apse at the eastern end. Barrel vaults stretch above, supported by columns that segment the space into rhythmic sections.

One of the most stunning interior moments is the altar space. Though partially reconstructed, it remains visually centered by a raised platform and surrounded by walls that still hold color and image.

The altar itself is framed by semi-circular steps, and a few of the mosaic tiles beneath your feet hint at what once covered the floor in full.

Look up, and you’ll see that many arches still cradle the faded geometry and figural art of the past—golden medallions, red-lined borders, iconographic panels.

Golden vaults flicker with narrative—fragments of saints, stars, and sacred geometry suspended in time

The contrast between high Byzantine art and the quiet erosion of time creates a powerful sense of dual presence: something fading, something held.

The burial chamber and beyond

Saint Nicholas was originally interred here, though his remains were reportedly taken to Bari, Italy, by Italian merchants in the 11th century. A sarcophagus inside the church—now empty—is traditionally believed to have once held his body. It rests in a side chamber that is dimly lit and often encircled by quiet visitors.

The tomb is carved with decorative reliefs and, while missing pieces, still suggests reverence. Along the surrounding walls, more frescoes depict bishops and saints. There’s a sense of enclosure here, as if the space breathes differently. The quiet is almost audible.

Though much of the original church is no longer intact, these fragments—from murals to sarcophagi to capitals—carry forward its essence.

A sacred pause in a layered day

Saint Nicholas Church offers something introspective. Our visit lasted about an hour, but its impressions stayed long after.

As part of the broader day tour, this site provides a powerful contrast to the natural and civic elements of nearby stops. It connects the deeply personal (a saint, a body, a story) to the broadly spiritual (ritual, worship, devotion).

Plan your visit

Saint Nicholas Church is located in Demre, within easy reach of Antalya. The best way to visit is by joining a guided day tour that includes Kekova and Myra—both archaeological marvels in their own right.

Our guide offered context, answered questions, and gave us the time to slow down, observe, and wander. The church is partially indoors, so it offers shade during hotter months, and it’s well-maintained compared to many ancient sites. Expect to walk on uneven surfaces and bring a camera that can capture low-light detail.